At this stage in the COVID-19 pandemic, uncertainty prevails. The greatest error that geopolitical analysts can make may be believing that the crisis will be over in three to four months, as the world’s leaders have been implying. As documented in The Atlantic and elsewhere, public-health experts make a compelling case that COVID-19 could be with us in one way or another until a vaccine comes on the market or herd immunity is achieved—either of which could take 12 to 18 months, unless we get lucky with a cure or an effective treatment before then. A long crisis, which is more likely than not, could stretch the international order to its breaking point. Even after a vaccine is available, life will not go back to normal. COVID-19 was not a black swan and will not be the last pandemic. A nervous world will be permanently changed.

COVID-19 is the fourth major geopolitical shock in as many decades. In each of the previous three, analysts and leaders grossly underestimated the long-term impact on their society and on world politics.

The end of the Cold War was a momentous event, but few saw the era of American hegemony and prosperity that would follow (the late Charles Krauthammer was a notable exception). In the 1992 presidential primary, one of the leading Democratic candidates, Paul Tsongas, had as his campaign slogan “The Cold War is over and Japan won.” That year, the U.S., suffering through a recession, saw Ross Perot make the strongest third-party bid of modern times on a platform of pessimism about the country’s trajectory.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, were widely seen as the effective end to the 20th century, but at the time many analysts argued that the long-term geopolitical impact would be limited. For instance, Michael Howard, the distinguished war historian at the University of Oxford, said that while the terrorist threat “will never entirely go away, I suspect that once we have hunted down the present lot of conspirators the world will return to business as usual.” Many others did forecast dramatic changes, of course, but few believed that the United States would be still fighting in the Middle East almost two decades later and that drones would revolutionize warfare.

American policy makers also underestimated the financial crisis of 2007–09, when they opted to let Lehman Brothers fail in September 2008 on the mistaken assumption that the decision would not trigger the collapse of other companies. European officials thought that the crisis had been made in the United States and would not affect global financial markets, and dismissed any concern that the euro zone may have its own vulnerabilities. The cooperation among G20 states, especially the United States and China, in responding to the crisis blinded many to the era of great-power competition that was about to unfold, as well as the nationalistic tendencies that would take hold in many governments. As the historian Adam Tooze has argued, in 2012, the populist wave had ebbed, but the biggest shocks—Brexit and Donald Trump’s election—lay in the future.

Now the COVID-19 pandemic has severe public-health, economic, and geopolitical ramifications, and many of those outcomes depend on how long the world will be in this suspended state. If the crisis lasts for a few months, the economy might well bounce back quickly, as aggregate demand returns.

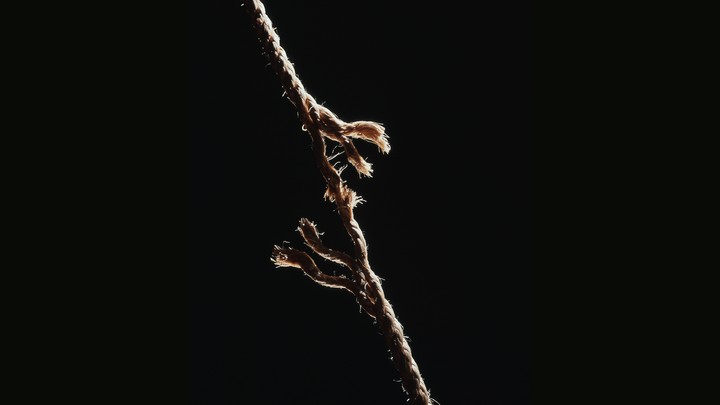

However, in a long crisis, countries will emerge profoundly changed. No one knows how exactly, but educated guesses are possible. A collection of massive domestic crises will collide, as health systems collapse or come close to it and governments struggle with double-digit unemployment, a severe recession or depression, plummeting revenue, increased expenditure, and mounting debt. Intermittent shutdowns, returns to work followed by retreats, and the continued suppression of demand are likely. The recession will look more like an L or W shape than a V. Companies and governments will run out of cash. They may default on debts, which will have ripple effects for other companies and could destabilize financial institutions.

Those countries that can afford to will be forced to turn to a stimulus package multiple times. Voters appear to be understanding of their leaders now, but the mood in six months or a year will be very different. As Warren Buffett once remarked of the markets, you see who is swimming naked when the tide goes out. A long crisis exposes which countries are truly competent. Which states can undertake the extensive, massive testing needed to have broad public-health surveillance and tailored isolation? Which will allow for the least restrictive economic measures? And which states can scale up industrial production to maintain resilient health-care systems and personnel all at the same time?

As a number of astute observers have noted, COVID-19 could end globalization as we know it, particularly if the pandemic is prolonged. Gérard Araud, formerly France’s ambassador to the United States, told me that when a crisis occurs, one should ask whether it breaks a trend or confirms it. “There is,” he said, “an assault on globalization” from multiple sources—the financial crisis, U.S.-China competition, climate-change activists pushing for people to buy local. COVID-19 piles on the pressure. Countries will be wary of outsourcing crucial medical supplies and pharmaceuticals to other countries. Supply chains more generally will be disrupted and will be hard to repair. Governments will play a much larger role in the economy and will use that role to rebuild a national economy instead of a global one—their priority will be domestic industry.

Some of these steps to restrict globalization are not only likely; they are necessary. Democratic governments cannot and should not tolerate a situation in which they lack the capacity to produce face masks, respiratory machines, and vital medications. The public will demand, and is entitled to, levels of redundancy in our manufacturing system. The challenge after this crisis ends is not to resist calls for reducing globalization, and the associated vulnerability, but to understand how best to reshape that process.

Meanwhile, those actors that have surveillance technologies may enforce quarantines on people who test positive for COVID-19 or other potential viruses as they emerge. For instance, leaders in Israel have empowered Shin Bet, the country’s internal security service, to use cellphone location data to track Israeli citizens during the outbreak. Others will surely follow, putting a new twist on vital questions about privacy, accountability, and safety.

A long crisis will not discriminate and will damage all of the world’s power and regions, although some countries will suffer more than others.

Much has been made of the opportunity that China has to supplant the United States as the leader of the international response to the pandemic, but COVID-19 is likely to be a strategic setback for China, particularly in its efforts to make inroads into Europe and other democracies. The Chinese Communist Party suppressed early warnings about the virus and an official at the Hubei Provincial Health Commission reportedly ordered a genomics company studying it to destroy “all existing samples,” causing public-health officials to lose invaluable time that could have been used to contain COVID-19. There is widespread concern that Chinese pressure has compromised the World Health Organization’s response to COVID-19 at at a time when multilateral cooperation was desperately needed. China subsequently allowed diplomats to falsely claim that the U.S. Army developed COVID-19 as a bioweapon and used it against China. The CCP is now trying to limit the damage of its errors by providing assistance to other countries in the form of face masks, respirators, and other supplies. Many see this aid as an act of confidence, but it might be evidence that the regime feels vulnerable and fragile.

Governments have welcomed China’s help, but they are under no illusion about the CCP’s responsibility. Ordinary people around the world, particularly in Europe, have suffered greatly from COVID-19—losing loved ones and their livelihood. They are unlikely to forgive or forget those who made mistakes that worsened their predicament, whether they are domestic or foreign. These matters will likely be litigated for years, with every action gone over with a fine-tooth comb. The damage to China’s international reputation may be the least of the CCP’s worries; the government’s legitimacy lies in its perceived effectiveness. China will also struggle to recover its high levels of economic growth while the world is in a deep recession. The country is reliant on global demand, and a protracted recession will demonstrate its interdependence with the rest of the world. If the crisis continues for 12 to 18 months, the virus will likely return to China, with all of the risks that poses for the regime.

However, China may also take advantage of a long crisis, particularly in hard-hit countries in Africa, Latin America, Central Asia, and parts of Southeast Asia where China’s footholds through the Belt and Road Initiative and its digital infrastructure will give it a head start when the time comes to rebuild after the crisis. Meanwhile, America’s industrial deficiencies and its failure to come up with a real alternative to BRI will handicap its capacity to help even if there were a wiser and more strategically minded president in the Oval Office.

The Middle East will likely pay a high price. The virus has decimated parts of the Iranian elite and spread from there to ravage much of the region. The Iranian regime appears incredibly fragile, but if the government falls, no one knows what comes next, given the lack of any organized opposition within the country. My Brookings colleague Tamara CofmanWittes told me that Egypt, Iraq, and Lebanon are also particularly poorly equipped to deal with what lies ahead. Two Egyptian generals died from COVID-19 almost two weeks ago, which suggests that the problem is much bigger than the government admits and has gotten into the army, one of the few institutions in Egypt that is capable of delivering services in a crisis. Revolution is unlikely—people will be sick, unable to organize, and President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has already systematically destroyed the opposition. Basic governing effectiveness in the whole region has been degraded over many years because of corruption and unresponsive dictators. After a long crisis, much of the Middle East will consist of zombie governments that are widely perceived as ineffective.

The European Union is a potential loser, although not inevitably so. One European official, who spoke with me under the condition of anonymity in order to talk frankly, said the crisis will be “transformative.” “Both the society and the international system we live in will be determined by how we act throughout the crisis,” the official said. The pandemic will “bring out the best and worst in us—maybe both simultaneously.” Health care is not a core competency of the EU, so all of the responses have been at the national level and will likely continue that way. As a result, borders have been closed and EU foreign ministries are negotiating with one another over the rights of transit for EU citizens to travel home through other member states. Another official told me that no leaders, except for President Emmanuel Macron, have shown interest in a cooperative response, at least in the first couple of weeks. They don’t oppose cooperation on principle; they are just so preoccupied with their own domestic crisis that no bandwidth is left for anything else. But recent days have brought signs of greater coordination and cooperation among EU member states.

The crunch for the EU will come on economics, which unlike health care is very much its business. The economic crisis of COVID-19 will be much worse than the euro crisis and will affect everyone—north and south, east and west. No European country can cope on its own, with the exception of Germany, which runs a surplus. The big question is whether Germany will agree to far-reaching reforms, such as common debt instruments (known as euro bonds) that the country has previously resisted. Italy, Spain, and other countries that suffered mightily in this pandemic and performed heroically will not respond well if the EU fails to move beyond the old orthodoxies of the euro crisis and doesn’t demonstrate the solidarity it prides itself on.

That brings us to the United States. COVID-19 is a disaster for Americans. The United States now has more cases than any other country. President Trump is singularly ill-equipped to handle the pandemic. For weeks, he parroted Chinese talking points that the virus was under control, and he predicted a good ending for the United States. He did not use the time he had to increase crucial medical supplies or prepare for a surge in medical personnel. In a long crisis, many people will die needlessly and the financial cost will be in the many trillions of dollars. The world has lost whatever confidence remained in the ability of Trump’s America to take charge. Leaders have watched in horror as the administration focused the bulk of its diplomatic efforts on renaming the virus. If Trump is reelected—and his polling numbers suggest he has benefited politically from the pandemic so far—substantial international cooperation is unlikely after the crisis ends and the recovery begins. Each country will go its own way.

The United States’ inaction has allowed the virus to spread inside its borders, and it has actively increased the risk to other countries. Sins of omission, however, are not generally as egregious as sins of commission, at least according to the rest of the world. Based on my conversations with officials from European and Asian allies, the United States has not figured much in other countries’ calculations. Europeans were vexed by Trump’s criticism of the EU, but didn’t care much about the travel ban. People had stopped traveling anyway, and European nations would soon close their own borders. Reports that Trump sought to purchase a German firm to monopolize a vaccine for the United States were more damaging, but the plan was thwarted by the German government. New reports, denied by the Trump administration and the company involved, that the United States is intercepting shipments of masks destined for Europe will raise similar fears. Generally, however, the United States is seen as a warning—an example, along with Brazil, of how a populist government is incapable of handling this crisis.

However, if Americans hit the reset button in the November election, a Biden administration will have the opportunity to turn the page and help lead an international recovery effort. This reset is not an option in CCP-ruled China.

As Evan Medeiros of Georgetown University recently pointed out, the only countries who have emerged from this crisis with their credibility intact so far are Asian democracies like South Korea and Taiwan. Germany is showing similar signs of competency, particularly in testing. They have offered a model for others to follow.

The real risk is that a long crisis will eviscerate international cooperation—among Western allies and between America and China—and leave a more anarchic world in which all are against all. As Gérard Araud pointed out to me, in 2019 the WHO published a plan to respond to a pandemic. Not a single major country followed the guidance. All did what they thought was necessary to protect their interests. Major powers will likely have less capacity—in terms of both materials and time—to cooperate on the geopolitical shocks that will surely occur during this crisis. They are completely preoccupied with their domestic problems and will be hard-pressed to invest time in a problem where their national interests are not directly threatened. And then there is the personal element. One official reflected to me that leaders are frequently moved to action only when they meet one another in person. Phone calls are simply not the same. It’s too easy to hang up, prevaricate, and turn back to the domestic problems.

The crisis no doubt reinforces power politics, particularly between the United States and China. But the pandemic also underscores the importance of cooperation with rivals on shared interests even as they compete ferociously in other spheres. During the Cold War, for instance, the United States and the Soviet Union worked together on the nonproliferation treaty and on arms control. Cooperation between rivals is not a simple matter and requires new strategies to create the conditions for a partnership to happen. Arms control was possible in the Cold War only because strategists understood the importance of second-strike survivability—the counterintuitive notion that your country was vulnerable to a first-strike nuclear attack if you could destroy all of your enemy’s weapons in one go (because it would give your enemy an incentive to strike first rather than to wait and retaliate after an attack). We have yet to invent similar concepts to advance cooperation on transnational issues, such as pandemics, with an authoritarian Chinese regime that has a system and worldview at odds with our own. For instance, is it better to allow such cooperation to be linked to other issues or ringfence it from everything else? How can you ensure sufficient levels of transparency, particularly when sensitive scientific matters are involved? That is a key task for the foreign-policy community.

No historical lessons will guide the world this time. The last global pandemic—the Spanish influenza of 1918–19—is not generally regarded as a driver of domestic and international politics over the 1920s and ’30s, likely because the world was already broken by World War I and less integrated than it is now. Never before has a single event upended everyone’s lives simultaneously and so suddenly. The longer the pandemic goes on, the more the world will change.