Americans are out of work. More than 20 million lost their jobs in April alone. Lines at food banks stretch for miles. Businesses across the country are foundering. Headlines scream that the coronavirus has brought about the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

The economic collapse of the 1930s, one of the defining traumas of the 20th century, is still the benchmark against which recessions are measured. And, for many Americans, the New Deal, launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, remains the standard for how the federal government should respond to a major national emergency. By the late 1940s, the United States had exited economic calamity and entered into an unparalleled period of national prosperity—with measurably greater income equality. America did not merely endure the Great Depression; its response transformed it into a richer and more equitable society.

Many hope to replicate that achievement today. But the success of the New Deal was built on more than all the agencies it spawned, or the specific programs it established—it rested on the spirit of those who brought it into being. The New Dealers learned to embrace experimentation, accepting failures along the path to success. They turned aside the ferocious opposition their bold proposals provoked. They organized supporters, and learned not just to lead, but to listen. And, perhaps above all, they pushed for unity and cultivated empathy.

The New Deal offers us more than a simple guide for returning to some semblance of normalcy. The larger lesson it offers is that recovery is a complex and painful process that requires the participation of many, not directives from a few. And that, ultimately, we’re all in this together.

During the great depression, as today, the nation’s initial response to disaster was crippled by the negative view of government held by then-president Herbert Hoover and his Republican Party. At the beginning of the century, the Progressive Era had led to greater government oversight of interstate commerce and the processing of food and drugs. But as secretary of commerce in the 1920s, Hoover had promoted an alternative ideal of voluntary regulation, whereby professional organizations and American businesses monitored their own affairs instead of being regulated by the federal government. That arrangement, which the historian Ellis W. Hawley dubbed the “associative state,” offered a sharp contrast to the progressivism that had preceded it.

Hoover was sworn in as president in March 1929, just months before the stock market crashed. But try as he might, he couldn’t get his associative state to master the challenge of the Great Depression. His miserable failure paved the way for Roosevelt’s landslide victory in November 1932.

Faced with a crisis of enormous proportion, Roosevelt reinvented how the nation did much of its business, most notably by involving the federal government in areas of American life that previously had belonged to cities, counties, or states—if to any governing authority at all. The New Deal succeeded in implementing policies at the federal level that had been percolating for years in reform circles, or that had been partly implemented by the most progressive states.

To ameliorate the immediate crisis, the federal government funded relief, jobs, and infrastructure. In the longer term, it established a new normal that included a national retirement system, unemployment insurance, disability benefits, minimum wages and maximum hours, public housing, mortgage protection, electrification of rural America, and the right of industrial labor to bargain collectively through unions.

These programs were rife with limitations. Social Security and unemployment insurance were tied to jobs, rather than citizenship; federal backing for mortgages redlined neighborhoods considered too nonwhite or immigrant; whole categories of workers were exempted from Social Security and fair-labor standards, such as those doing domestic and agricultural labor; and many necessities for a decent life, such as paid sick days and health coverage, were left to the discretion of employers or the bargaining brawn of unions. Yet flaws and all, the New Deal constructed a social safety net that undergirded a long period of growth and prosperity.

But if we want to use the New Deal as a model for creating opportunity out of catastrophe, we will need to understand more than just its policies and programs. Building a new and improved United States, post-coronavirus, will require understanding how Roosevelt and his associates, labor leaders and activists, and ordinary Americans combined their efforts during the bleakness of crisis to build a better future. We need to know not just what they did, but how they pulled it off.

The new deal was experimental and incremental—not ideological. Roosevelt and his advisers were far from the clairvoyant visionaries of legend. They never had a master plan. Rather, in the administration’s first 100 days, they implemented a flurry of laws and regulations. If those programs worked, they remained. If they didn’t, they were dropped, to be replaced by others.

The National Industrial Recovery Act, for example, with its voluntary codes of fair competition for prices and wages and limited encouragement of collective bargaining, proved inadequate, and then was ruled unconstitutional. The administration quickly developed alternatives, including the National Labor Relations Act (known as the Wagner Act), which offered a clearer path to unionization.

Not until after 1935 did the New Deal’s welfare state of Social Security, unemployment insurance, and public housing emerge. And many of its initiatives failed, such as when a premature rollback of federal programs precipitated the “Roosevelt recession” of 1937, boosting unemployment back to frighteningly high levels. Even the Harvard professor Alvin Hansen, FDR’s trusted economic adviser, admitted, “I really do not know what the basic principle of the New Deal is.”

Indeed, disagreements rent the Roosevelt White House. For example, some economic planners wanted a recovery that revived the old Progressive-era crusade against monopoly, while others favored regulating businesses regardless of size, or taking a Keynesian approach of using the state’s fiscal powers to increase consumption. By the late 1930s, the Keynesians had won out. John Kenneth Galbraith, then a young professor, recalled that, as late as 1936, the acceptance of the rules of classical economics was “a litmus by which the reputable economist was separated from the crackpot.” A year later, “Keynes had reached Harvard with tidal force.” The point is that no well-prepared road map set the New Deal’s course.

Roosevelt was also remarkable for the manner in which he successfully disarmed most of his political opponents. It may be tempting today—with our stalemated politics, deeply divided electorate, and inflammatory media—to imagine that FDR, who won by landslides in 1932 and 1936 and by a comfortable margin even when seeking an unprecedented third term in 1940, enjoyed the luxury of a national consensus. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Roosevelt administration was attacked from the right by disapproving Republicans, business leaders who vowed to destroy the “socialist” New Deal, wary Southern Democratic members of Congress, and the hugely popular Roman Catholic radio host Father Charles Coughlin. Coughlin’s Golden Hour of the Little Flower program regularly drew an audience of more than 30 million into his anti-Roosevelt, anti-Communist, anti-Semitic, isolationist, and conspiratorial miasma.

On the left, Roosevelt faced small but effectively organized communist and socialist groups, as well as miscellaneous third parties like John Dewey and Paul H. Douglas’s League for Independent Political Action. Much more threatening was Huey Long of Louisiana. The populist—and wildly popular—governor and then senator quickly abandoned Roosevelt as too cautious, mounting his more redistributive “Share Our Wealth” program. Long reached millions through a national network of clubs and his own radio broadcasts. Roosevelt feared Long as a dangerous demagogue until his assassination in September 1935, but Long’s indisputable popularity likely pushed FDR leftward.

Roosevelt responded to these challenges from the right and the left by justifying the New Deal in uncontroversial, almost nonpartisan terms. Although his message could fluctuate depending on which enemies he aimed to vanquish—for example, denouncing capitalist elites as “economic royalists” in his 1936 speech to the Democratic National Convention so as not to be outflanked on the left—FDR typically justified the New Deal as the pursuit of “security against the hazards and vicissitudes of life” or the protection of the “four freedoms” of speech, worship, want, and fear. And not to be outdone by Father Coughlin or Long, Roosevelt became a master himself of the radio, brilliantly using his many fireside chats to establish an intimate relationship with the American people.

Roosevelt also learned that to lead, he needed to listen. The social and political changes of the New Deal were built by mobilizing ordinary Americans as Democratic Party voters and rank-and-file union members. The New Deal was no top-down revolution. Democratic politicians as well as union organizers quickly discovered that they needed to focus on the real problems people faced, and to respond to their preferences.

Before the New Deal, many working people lived political lives circumscribed by their local party, whether Democrat or Republican. First- or second-generation immigrants were loyal partisans, if they even voted at all. Few African Americans in the Jim Crow South could vote. Those who traveled north in the Great Migration of the 1910s and ’20s spurned the Democratic Party as the instrument of their southern oppressors and the enemy of the party of Lincoln, which many of them now eagerly supported.

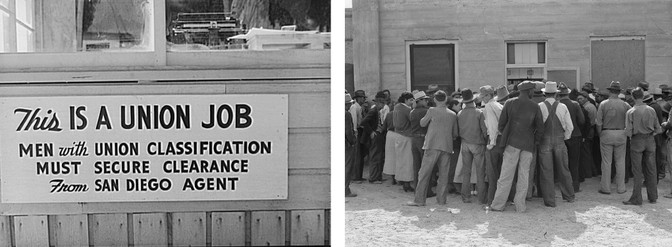

Within industrial workplaces, unions—to the extent they existed in the 1920s—were made up of elite craft workers, mostly white and native-born, who sought to limit the opportunity and mobility of the more numerous, and more vulnerable, nonunion workers. Labor organizers suffered a series of stinging defeats in 1919, after which unions seemed to hold little promise for the less skilled workers who powered the mass-production plants that were making the U.S. the 20th century’s “workshop of the world.”

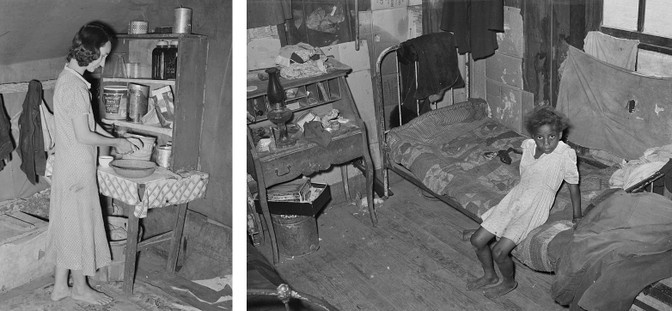

Fearing reprises of the unionization drives that had followed World War I, some employers mounted paternalistic welfare programs in the 1920s, touting benefits such as paid sick leave and vacations, pensions, stock ownership, group life insurance, and employee representation plans. But companies rarely backed those promises with the level of financial investment required to deliver those benefits to more than a fraction of their workforce. Workers relied instead on inadequate safety nets provided by their ethnic, racial, and religious communities, which quickly failed under the strain of the Great Depression.

By the time Roosevelt won a second presidential term, in 1936, the world had transformed. Many of those in need were taking full advantage of federal relief and jobs programs sponsored by the array of New Deal agencies, including the FERA, CWA, PWA, WPA, NYA, and CCC. By addressing the needs of Americans, Roosevelt earned their support. Faced with the enormity of the Great Depression, working-class Americans were voting in record numbers—and they voted for the Democratic president. Black voters were even replacing the motto “Stick to Republicans because Lincoln freed you” with “Let Jesus lead you and Roosevelt feed you.”

Working people also drove a massive effort to unionize industrial laborers across many sectors, coordinated by the newly founded Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), whose success was facilitated by the Wagner Act. By 1940, in the manufacturing stronghold of Chicago, one in three industrial workers belonged to a union, whereas 10 years earlier hardly any had. The story was much the same in Detroit and Flint in Michigan, Cleveland and Akron in Ohio, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, and elsewhere. Workers who only a few years before had felt little connection to Washington, D.C., and excluded from national unions now identified with the federal government and nationwide political and labor movements.

Through their participation in the Democratic Party and unions, workers helped to ideologically reorient both of these new centers of political gravity. Although from local precincts to the Democratic Party headquarters and from shop floors to the CIO’s inner circle, leaders mattered, those with power had to contend with a rank and file that knew its own mind.

This was particularly evident in the labor movement. Left-wing activists were crucial organizers of Communist Unemployed Councils, socialist Workers’ Committees on Unemployment, hunger marches, demonstrations outside relief offices, and emerging unions. But in the end, despite all the hardships of the Great Depression, few workers bought into the anti-capitalist message.

The Communist organizer Steve Nelson recalled how he and his comrades had begun by “agitating against capitalism and talking about the need for socialism.” Quickly, however, they figured out that working-class people were more concerned with their daily struggles. “We learned to shift … to what might be called a grievance approach to the organizing,” he said. “We began to raise demands for … immediate federal assistance to the unemployed, and a moratorium on mortgages, and finally we began to talk about the need for national employment insurance.” In fact, partly inspired by the empty promises of their employer’s welfare-capitalist schemes of the 1920s, working-class Americans came to embrace what I have elsewhere labeled “moral capitalism.” While workers benefited from the organizing experience of radical leaders, they more often opted for liberal goals than for radicalism, preferring a more just capitalist order over any alternative.

The new deal’s success had one final, and crucial, ingredient: the cultivation of empathy.

For labor leaders, it was a practical necessity. Herbert March, a Communist organizer in Chicago, was typical in worrying that “it would not be possible to achieve unionism because you had the split of black and white and too many nationalities … that they [employers] would play against each other.” These sorts of ethnic and racial divisions had helped doom the 1919 organizing drives. Unless unions could inculcate an ideal of racial inclusion and class solidarity, white working people might well retreat to their segmented ethnic and racial worlds and push their African American co-workers back into the arms of employers as strikebreakers.

To avoid that danger, the leftist leaders of the CIO worked hard to cultivate what I have called an inclusive “culture of unity” within the evolving union movement. A black packinghouse worker named Jim Cole told an interviewer in 1939 that the CIO had “done the greatest thing in the world” by bringing workers together, and dispelling the “hate and bad feelings that used to be held against the Negro.” Enlightened activists helped working people transcend their prejudices at a crucial moment.

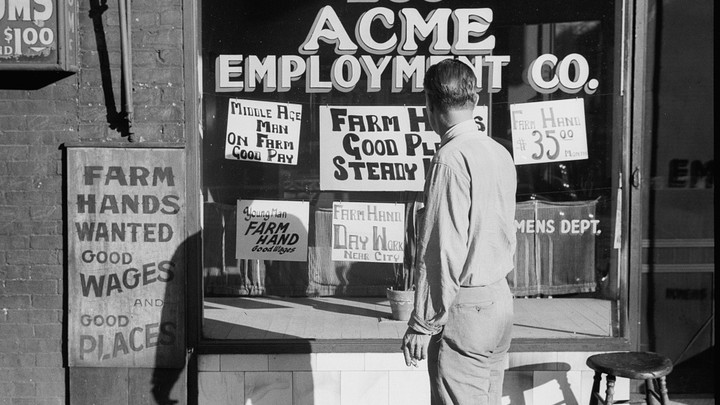

The New Deal, too, made this work central to its project. Alongside their many new and unfamiliar agencies, the New Dealers set out to document how Americans were weathering the Great Depression. These undertakings were spurred by multiple motives, including generating publicity for New Deal programs and employment for out-of-work artists and actors. But most fundamentally, these projects educated people about their countrymen and -women and bred empathy. “We introduced America to Americans” is how Roy Stryker, the head of the Farm Security Administration, put it many years later.

The FSA images taken by such legendary photographers as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Gordon Parks, and Ben Shahn are probably the best-known such initiative, but almost every New Deal agency mounted its own photography project to document its impact on the American people. The WPA’s Federal Writers’ Project sponsored life and oral histories, ethnographies, and portraits of diverse cultural communities, including recent immigrants, Native Americans, and African Americans. And the Federal Theater Project produced documentary plays in its “Living Newspaper” performances.

If these lessons of the New Deal apply to our own moment, then so does one more: There will be no easy return to normalcy. Despite all of the New Deal’s interventions, unemployment was still disturbingly high on the eve of World War II. The massive stimulus of global war was what finally lifted the United States out of depression, although that war brought with it additional years of deprivation and sacrifice. Moreover, many Americans would never overcome the trauma of the Depression, and would have to be prodded into a postwar era that depended more than ever on consumer spending to deliver widespread prosperity.

What form the economic recovery from COVID-19 shutdowns will take remains difficult to predict. The strategies and programs of the 2020s won’t be the same as those of the 1930s. The enormous growth of consumption as a percentage of GDP, from a low of 49.5 percent in 1944 to roughly 70 percent today, has led policy makers to prioritize a ramping-up of consumption—often prematurely—over job creation. National leaders seem to prefer sending checks to the jobless over providing them with jobs. Brick-and-mortar stores, restaurants, and other vendors of personal services, which were already struggling with the shift to online shopping, have been particularly hard hit. Their slow recovery will not only remain a drag on the larger economy, but will also affect the vitality of public life, which often revolves around commercial districts.

Moreover, there is a real risk that the downturn will exacerbate the inequalities already present in the American economy—in jobs, income, health care, housing, and education. Consumption could continue to shift toward the largest sellers, like Amazon, squeezing out smaller businesses. The nation’s workforce might then become even more unequal, with small numbers of salaried executives at the top and armies of low-skilled, hourly warehouse employees and package deliverers with limited benefits at the bottom. Already, the COVID-19 crisis has made apparent shameful racial disparities that are taking an extraordinary toll on communities of color.

And the current disaster could also deepen our divisions. Perhaps the greatest obstacle to solving our social ills has been the intense partisanship and vicious scapegoating that has paralyzed the polity. We are fractured along many lines. What once were civil disagreements over the size of government, the reach of the safety net, or the relative benefits of taxing versus incentivizing business entrepreneurship have become insurmountable divides.

But if we cannot simply copy the New Deal’s programs and apply them to our contemporary challenges, we can still take inspiration from the spirit that animated them. We can set aside ideology in favor of experimentation, fend off partisan attacks with appeals to higher principles, focus on the needs of ordinary workers, and deliberately cultivate the unity and empathy required to forge an effective coalition to do battle with the coronavirus and economic devastation.

This last point is perhaps the most important, and it may be the most difficult. Empathy, after all, has been badly missing in the United States in recent decades.

Perhaps we’ve made a start. The iconic images of this pandemic are of nurses, doctors, and EMTs caring for the sick. Nightly displays of thanks echo in many parts of the country. Grocery-store clerks are recognized as heroes. The coronavirus’s harsh lesson in our shared vulnerability to disease—that we are all safe only when everyone is healthy—could become the basis for a broader recognition of our shared fate as Americans. Learning that lesson may help us rebuild our society into one that treats everyone as essential.