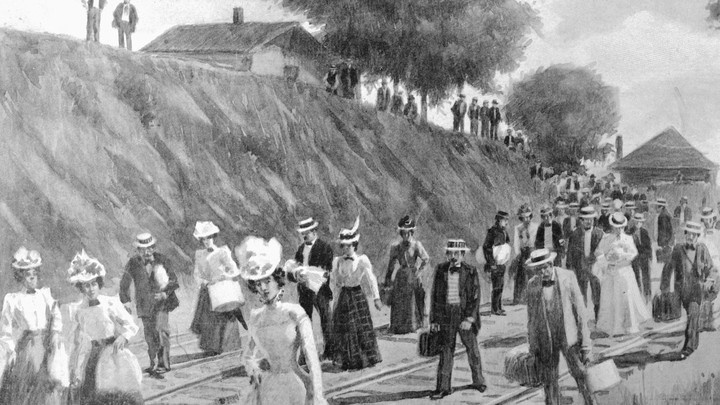

When a young man named Isaac H. Charles arrived in yellow-fever-ravaged New Orleans in 1847, he did not, as one might expect, try to avoid the deadly disease, which killed as many as half of its victims at the time. He welcomed yellow fever—and, more importantly, the lifelong immunity he would have if he survived it. Luckily, he did. “It is with great pleasure,” he wrote to his cousin, “that I am able to tell you with certainty, that both [my brother] Dick & I are acclimated.”

For men like Charles, “acclimation,” to use the language of the time, was not so much a choice. It was the so-called “baptism of citizenship,” the key to entry to New Orleans society. Without immunity to yellow fever, newcomers would have difficulty finding a place to live, a job, a bank loan, and a wife. Employers were loath to train an employee who might succumb to an outbreak. Fathers were hesitant to marry their daughters to husbands who might die. The disease is caused by a virus spread through mosquito bites, and it causes chills, aches, vomiting, and sometimes jaundice, which gives yellow fever its name. The people of 19th-century New Orleans did not fully understand the biology of the disease, of course, but they noticed that their fellow residents seemed to become immune after a first bout. Thus, even the president of the New Orlean’s Board of Health once proclaimed in a speech, “The VALUE OF ACCLIMATION IS WORTH THE RISK!”

When yellow fever swept through New Orleans two centuries before our current pandemic, it made immunity a form of privilege—one so valuable, it was worth risking death to obtain.

The outbreaks exacerbated existing forms of inequality too. New immigrants to the city disproportionately bore the risks of acclimation to yellow fever, eager as they were to find jobs. (The wealthy, meanwhile, emptied out of the city during summer yellow-fever season.) Enslaved people who were acclimated were worth 25 percent more—their suffering turned into financial benefit for their owners. “Diseases lay bare who belongs in society and who does not,” says Kathryn Olivarius, a Stanford historian who studies yellow fever in the antebellum South.

These days, Olivarius told me, “I feel like I write about yellow fever by day and worry about coronavirus by night.” The diseases are not perfect analogues, but in a world upended by a pandemic that has killed more than 137,000 people, immunity may once again become a dividing line. The United Kingdom’s health minister has proposed “immunity certificates”—wristbands, perhaps—to identify people recovered from COVID-19 who can go back to normal life. Germany has floated “immunity passports” to get the immune back to work. Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said last week that the United States is considering a similar idea.

It is still unclear how these schemes would work—not least because it’s unclear how long immunity to the coronavirus even lasts. And as my colleague Ed Yong writes, the immunity tests are not perfectly accurate, which could give some takers a false sense of security. This virus and the disease it causes are both so new to humanity that scientists are still trying to answer basic questions about them.

The technical hurdles of biology aside, a system to keep track of the immune requires a massive new logistical understanding. “It’s so complicated to think about how to manage all of these things,” says Jeffrey Kahn, a bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University. For example, Kahn says, consider how conditioning free movement or employment on immunity could very well lead people to falsify immunity certificates.

If the government allows the immune to return only to certain jobs or if employers prefer to hire those who are immune, that could also create a set of perverse incentives to deliberately get infected with COVID-19, especially for the young and otherwise healthy who might think it’s worth the risk for a job. Unemployment has shot to record numbers during the pandemic, after all, and many people who have lost their jobs are those who can least afford to. They might see immunity as a way out of unemployment, despite the dangers.

“People in already economically, socially precarious positions have to make choices that they should never have to make,” Olivarius said. And this, unfortunately, is familiar to her as a historian of yellow fever. Charles was one of the lucky ones to recover from the disease in New Orleans; yellow fever was responsible for 75 to 90 percent of the deaths of immigrants like him.

The recent pandemic, Olivarius said, has made her feel more viscerally how her 19th-century subjects must have felt with an invisible disease striking down their loved ones. The uncertainty, the proximity to death, the obsession with documenting their health in endless letters—it’s become our 21st-century way of life too.

/media/img/mt/2020/04/0420_Ramos_Martin_RecoveryPlan/original.png)