But the new strategy for China is profoundly different from the political containment and détente strategies that the United States followed during the real Cold War. The competition with the Soviet Union and its allies was fundamentally political and military. A spiraling nuclear arms race converged in central Europe where two opposing military alliances, NATO and the Warsaw Pact, were poised for war. Moscow aggressively promoted the spread of communism, opportunistically fomenting and supporting revolution and guerilla wars around the world.

The Soviet Bloc, however, could never successfully compete with Western democracies in the marketplace. The rigid, centrally planned approach to economics pursued by Soviet-style communism did not hold a candle to the dynamic free-market economies of the West. The Soviet Bloc operated within its own closed economic world, generating far less prosperity than market-based economies. Ultimately, the Soviet system collapsed of its own weight, strangled both by its centrally planned dirigisme, and Western alliance trade controls that denied the Communist Bloc access to advanced technology and products. Anyone from the United States who traveled to Russia after the Soviet Union’s collapse in the early 1990s thought that they had walked into a time warp, a country stuck in the 1950s. In the end, the Soviets did not have the economic ability to keep up the military competition with the United States and its allies. The arms race bankrupted the Soviet Union and its centrally planned communist, economic system.

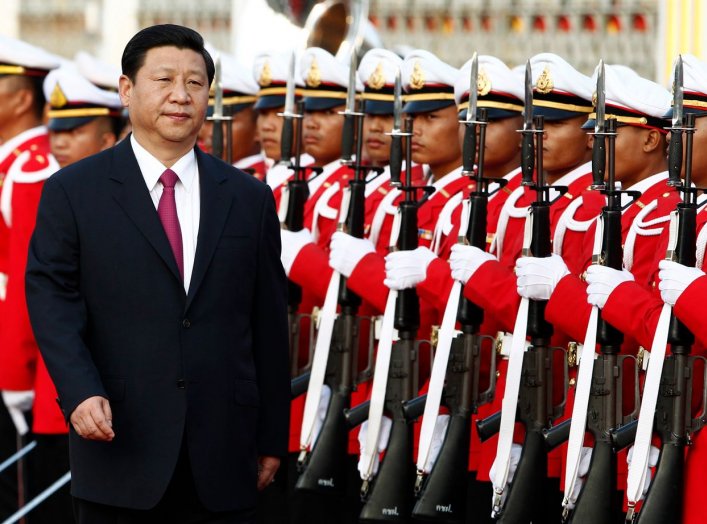

The current situation with China bears no resemblance to any of this. China is the world’s largest, market-based economy in purchasing power parity terms. The Chinese challenge is overwhelmingly a question of market governance. Unlike the former Soviet Union, China does not seek to impose or spread its style of communist rule on other countries (other than Taiwan), either by military means or political persuasion. China’s nuclear arms inventory is a fraction of that of the United States or Russia, adequate only to survive a first nuclear strike and retaliate. China’s economy is not centrally planned under Soviet-style communist principles. China’s economy has leaped to the top by exploiting and manipulating what the administration describes as the global economy’s “free and open rules-based order.” China is now the leading exporting country in the world and the second-largest importer after the United States. It has cynically manipulated free market rules to achieve its long-range goal of global economic dominance under an authoritarian communist party model more reminiscent of German-style fascism than Marxist socialist doctrine, or Soviet-style central economic planning and control. Like Nazi Germany, China espouses a form of (Han centered) ultra-nationalism, marked by dictatorial powers, suppression of dissent, and overwhelming regimentation of society and the market economy to serve the ends of one-party rule under a benighted leader.

But, unlike the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany, China’s military objectives have so far proven to be far more limited than its economic ambitions. China’s priority military focus is confined to the zealous defense of its territorial borders, including dominance over its littoral waters, the Yellow, East and South China Seas. While China’s navy today is the world’s largest, having built four warships for every one built by the United States over the last ten years, those ships are concentrated in waters near its coast, not patrolling throughout the world like those of the U.S. Navy.

In the mid-1990s, China fired missiles into waters close to Taiwan, trying to intimidate that country’s first democratic, presidential election. In response, the U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM) sent two carrier battle groups into the Strait of Taiwan. Confronted with that U.S. naval might in those days, China had no choice but to back down. Chinese missiles stopped falling and Taiwan held its election. The balance of naval power in the region since then has dramatically shifted to China’s favor. PACOM would not sail modern carrier strike groups today into the Taiwan Strait to deter China. But while China’s navy, backed by thousands of missiles ashore, has grown far more powerful, its aims so far remain defensive to protect the homeland and adjacent waters, leveraging advantage from its interior lines of defense.

The Trump administration’s new policy approach to China marks a subtle recognition of these objective realities. The administration is marshaling a foreign policy strategy that is centered more on economic than military imperatives.

The number one national security challenge posed by China according to the new policy is not existential or military but rather “state-driven protectionist policies and practices [that] harm United States companies and workers, distort global markets, violate international norms and pollute the environment.” Mercantilism, intellectual property theft, cyber hacking, discriminatory trade practices, business corruption, financially destabilizing, opaque loans to foreign governments, are listed as actions that compel a systemic policy response by the United States. While the strategy notes Chinese challenges to American values and military security as other concerns, it is clear that the major focus of the new national security policy is on economic governance challenges. The strategy also strikes a stark realist perspective by underscoring that it is not aimed at overthrowing or changing China’s communist regime, leaving that question of internal governance to “the Chinese people themselves.” This approach contrasts with old Soviet Cold War policy, (at least before the advent of Nixon/Kissinger détente) when effecting regime change in at least some communist countries was considered a possible goal.

To implement its new policy, the Trump administration is pursuing a number of different avenues. The military aspects of the initiative will be relatively limited, calling mainly for increased military cooperation with allies, continued freedom of navigation cruises in the South China Sea (something that can be handled by one or two smaller warships such as frigates or destroyers), and continued development of precision strike missiles, drones, cyber and space capabilities. The financial investment necessary to support this kind of military commitment should be considerably less than what was spent during the Cold War and after on nuclear weapons, carrier battle groups, advanced stealth bombers and fighters, and weapons and equipment for mass infantry combat. The strategic competition with China is envisioned to be fundamentally peaceful, focused in the realm of economic and global governance.

The steps in the process of implementation by the Trump administration to address China’s unfair economic governance practices are manifold. They range from curtailing China’s access, under its “Military-Civil Fusion” strategy, to advanced U.S. technologies including telecommunications; to aggressive prosecution for trade secret theft; to restrictions on Chinese foreign direct investment in sensitive U.S. infrastructure and supply chains; to more aggressive enforcement of foreign agent registration laws on Chinese government agents in the United States; to combatting the U.S. sale of Chinese counterfeit products and fentanyl; to restricting access of students with connections to China’s military to sensitive academic fields; to imposing tariffs to protect strategically important U.S. industries such as steel and aluminum; to more crackdowns on illegal Chinese dumping and subsidies for products sold to the U.S. market.

While these measures are comprehensive, none involve a U.S. Cold War-style military buildup to confront China aggressively immediately off its coastline. The Trump administration’s new policy initiative makes it clear that the United States is not trying to impose regime change on China, however much the United States abhors its authoritarian practices. While the United States will continue to stand up diplomatically for human rights and respect for the autonomy of Taiwan and Hong Kong, the fact is that short of nuclear war, there are limits to what the United States (and its allies) can impose by military will on China. In the years ahead, the key to global stability will be the pursuit of effective economic diplomacy and trade policy, persuading China to practice fair and honest governance in the global marketplace consistent with General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, bilateral obligations and international norms. The national security structure of the United States will need to adjust overall. The role of the military in the conduct of foreign affairs, including powerful regional combatant commands, will likely be less compared to the Cold War and the post—9/11 eras. Future National Security Advisors at the White House may also be less likely to be generals, and more likely to be economists and international trade experts. While keeping its guard up, America will become less Sparta and more Athens. A new Cold War is not beginning.