Bill de Blasio has long been spoiling for a fight, just not the one now before him and his city. When he became the 109th mayor of New York, on a colorless winter day in 2014, he promised to lead a struggle against “injustice and inequality.” Although he has had some genuine successes, he has failed to turn the city into a Copenhagen-on-the-Hudson. He hasn’t turned it into Caracas, either. New York is pretty much the same global metropolis it was when he took over.

Aware that his progressive ambitions have been frustrated, de Blasio has complained that legions of enemies—conservatives, capitalists, newspaper headline writers—are arrayed against his vision for the city.

However determined these forces have been to undo him, they are not responsible for what New York magazine called, on March 26, “his worst week as mayor.” Worse than the week in 2014 when two police officers were shot and killed, degrading his relationship with the department. Worse than the many weeks in 2016 of overlapping ethics investigations, which threatened to ensnare the mayor and his top aides.

The enemy, this time around, is very small, in contrast to de Blasio, who is not only tall but somehow enlarged by his own ungainliness (he can perform the impressive feat of filling a room without commanding it). In that enemy’s arsenal is a glycoprotein that protrudes from its surface like the quills of a porcupine. In 1965, researchers decided the glycoproteins made the viral particle they were scrutinizing look like a crown. Resorting to Latin as doctors do, they called it a corona.

Trying to lop off glycoproteins is not why de Blasio got into politics. De Blasio has always looked past New York, has never hidden his national ambitions. Six months ago, he was a moderately credible presidential candidate. I went to a de Blasio event in Des Moines, Iowa, and was struck by the adulation directed his way. I was even more struck by how genuinely happy de Blasio seemed. After concluding his stump speech, he stayed for a good half hour, meeting voters, shaking hands. Through it all, he smiled.

Now he is telling people to wash their hands and cough into their elbows. Of course, every politician in the United States is lathering constituents in the same hand-washing, elbow-coughing advice. But de Blasio seems more irritated at having to do so than most.

He has indicated that irritation with the subtlety of a Times Square advertisement. As all New York tabloid readers know, de Blasio trekked daily from Manhattan to Brooklyn to exercise at the same gym he frequented before becoming mayor. De Blasio continued to travel back to Brooklyn right up to the day he ordered all gyms closed. That last gym trip has become the stuff of legend, an act of petulant defiance from which de Blasio’s reputation will probably never recover.

Leadership is never more apparent than when it is missing. De Blasio was slow to recognize the danger, telling New Yorkers to keep to their ordinary routines—as he did his—even after the World Health Organization had declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic.

De Blasio has often been spotted walking in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, near his old house, even as most New Yorkers are confined to their homes and some New Yorkers fight the coronavirus in overcrowded hospitals. You may have heard that there are parks in Manhattan. Gracie Mansion, where de Blasio lives, is located inside one, an esplanade that follows the East River as it opens gloriously to embrace the Bronx and Queens. The same convoy of SUVs that whisks him to Brooklyn could get him to Central Park in five minutes tops.

I imagine that de Blasio knows where Central Park is, more or less. That’s rather beside the point. Throughout the coronavirus crisis, he has evinced no passion for New Yorkers, or New York. When he gave an interview to MSNBC last Sunday, what marked his face was not exhaustion but exasperation.

In fact, he hasn’t given up on the possibility that he can do nothing in this crisis other than attack Trump, just as he did in his days as a presidential contender. “He’s not acting like a commander in chief, because he doesn’t know how,” de Blasio said on MSNBC two weeks ago. “He should get the hell out of the way.” Even so, he has continued to plead with Trump to do everything in his power to help New York, making for an odd combination of bluster and helplessness.

Much has been wanting about Trump’s response to the outbreak. But de Blasio’s fulminations against Trump are clearly meant to divert from his own failures of leadership. De Blasio equivocated on obvious measures like closing schools. He could not even bring himself to close the city’s playgrounds. When these were finally shuttered, it was by decree of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. De Blasio went along with the plan reluctantly—“I respect that,” he said of the decision—like a child being dragged to the dentist by his determined dad. On WYNC on Friday, he said researchers had only discovered “in the last 48 hours” that asymptomatic people can spread the disease. If Trump made the same preposterous claim, there would be howling calls for impeachment, renewed questions about his state of mind. Public-health professionals have known for months how the coronavirus spreads and who can do the spreading. If de Blasio didn't know, the fault is fully his own.

Abandoned by both Trump and de Blasio, New Yorkers have turned to an unlikely savior in Cuomo, who until this new coronavirus came along had proved a confounding member of the Democratic establishment. That is partly a function of lineage: He is a Cuomo, yes, but he is not his father, Mario, whose speech at the 1984 Democratic National Convention was so eloquent an articulation of liberalism that it has not been rivaled in more than three decades. Andrew Cuomo has never quite explained what kind of liberal he is, other than the kind who wants power.

Cuomo considered a 2020 presidential run, then thought better of it. This was not a year for the kind of unsexy managerial expertise that tends to reside in a governor’s mansion. The voters wanted fiery rhetoric to match Trump’s. De Blasio, in this limited sense, was up to the task. “Donald Trump must be stopped,” de Blasio said in his announcement video. “I’ve beaten him before, and I will do it again,” the mayor said, leaving others to divine where those victories over the president had come.

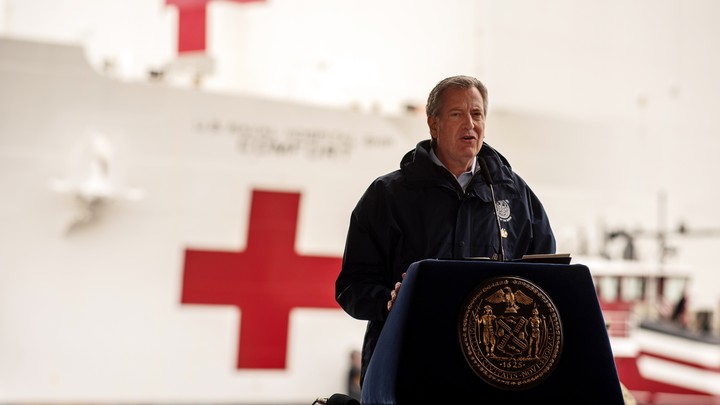

The pandemic, however, has already changed the political calculus, and now some people are clamoring for Cuomo to replace Joe Biden, who leads in the delegate count for the Democratic nomination. How that would happen, nobody credible has a clue. And it probably won’t. But every time Cuomo takes to a podium in his windbreaker, such hopes are revived.

What, exactly, has Cuomo done? Maybe, in aggregate, not so much. Then again, the answer really depends on what you mean by done. Cuomo can no more defeat the coronavirus on his own than General Patton could single-handedly beat back the Germans at the Battle of the Bulge. For that matter, no one expects de Blasio to hijack a Columbia University lab and emerge, after a feverish night, with a vaccine. People want decency, honesty, and compassion. They want him to understand that something greater than his gentle 90-minute communion with a stationary bike in Brooklyn hangs in the balance.

Many people are saying (to borrow a phrase) that Aristotle understood politics as well as any human who has ever lived—Nate Silver notwithstanding. A concept central to Aristotle’s political philosophy is phronesis, which he defined as “having the right feelings at the right time on the right occasion towards the right people for the right purpose and in the right manner.”

Politics is about getting it. The only reason Cuomo is being celebrated is because he gets it. He understands what is happening and why, what may happen, what can be done, what must be. Cuomo has the phronesis thing. He feels your pain. De Blasio is phronesis-free. He seems to have the opposite quality, an almost impressive ability to strike the wrong tone—the tone of a liberal warrior before the world changed.

Because New York remained prosperous and safe during most of de Blasio’s generally hapless tenure as mayor, his constituents have forgiven the man his shortcomings, whether these involve ethical lapses or embarrassing displays of national ambition. But of the many luxuries the coronavirus has effaced, one is the tacit acceptance of incompetence. New Yorkers no longer have any patience with rhetoric, nor any taste for purposeless fulmination. De Blasio rails against Trump on cable news and it means nothing, because people are dying in Elmhurst and Flatbush. The people need something, they crave it. Maybe it is the thing Aristotle wrote about, or maybe it is something else entirely. Maybe it is a ventilator; maybe it is hope. Whatever it is, Bill de Blasio is simply unable to give it to them.