The shutdown of non-essential services to control the spread of COVID-19 has had severe economic consequences in Canada, including the loss of nearly two million jobs in April.

As economists, we are analyzing the effects of COVID-19 on Canadian labour markets in an ongoing research paper by asking the following questions:

What are the short-term impacts of COVID-19 on unemployment, hours and wages?

Do the economic consequences vary across demographic groups, union status and immigration status?

Are there larger effects for occupations that are more at risk of contracting the virus?

Are there smaller effects for individuals who can easily work from home? What is the impact on the labour market for essential workers?

Which occupations and industry are seeing the biggest changes in economic outcomes?

Understanding which workers are most affected by the coronavirus economic shutdown will help guide policy and Canada’s economic recovery.

The hardest hit

COVID-19 has had a severe impact on Canadians in terms of unemployment rates, hours worked and labour force participation — the proportion of the adult population currently employed or seeking employment.

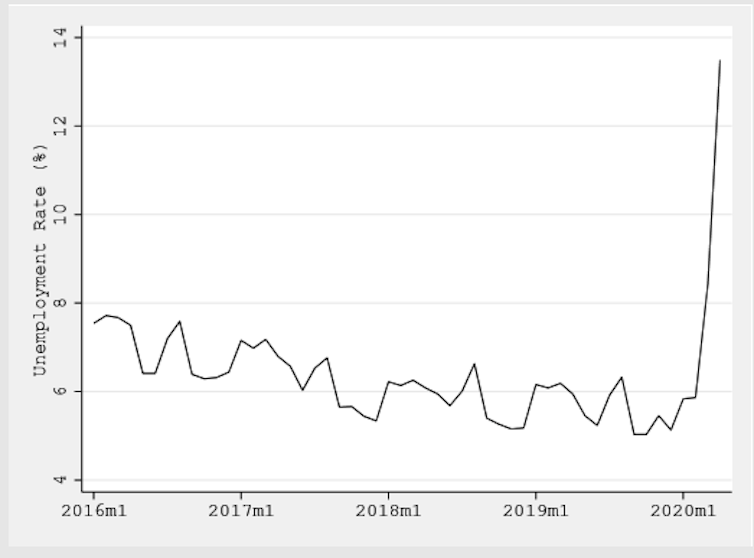

Job losses have been staggering. The unemployment rate more than doubled to nearly 14 per cent between February and April.

The unemployment rate in Canada between January 2016 to April 2020. The x-axis represents time in months, with m1 representing January. (Data from Statistics Canada. Calculation by authors) But this measure is an understatement of how dire the situation is — labour force participation fell by five percentage points to 59.8 per cent over the same period. These individuals aren’t included in unemployment calculations, which only capture people who are looking for work. This means that a fall in labour force participation translates to people not searching for work. Not only have people lost jobs (increased unemployment), they have also stopped looking for work (decreased labour for participation).

One concern is that COVID-19 might increase existing inequalities in the Canadian labour market. For example, if minimum wage earners lost their jobs, it could affect their ability to pay for rent or other essentials. Knowing which workers are more affected will help guide effective policy recommendations.

Our results suggest that the negative impacts of COVID-19 are more pronounced for workers who are younger, unmarried or less educated. We also find evidence that workers in unions are less likely to be negatively affected. In sum, our results suggest that COVID-19 may be deepening already existing inequalities.

COVID-19 has negative labour market outcomes for both men and women, with no discernible differences between the two, suggesting that the shutdown has not increased gender inequalities. Our results also indicate that women without children have experienced slightly larger job losses, reductions in hours, wages and labour force participation than mothers.

We find that immigrants and non-immigrants similarly experienced a near doubling of the unemployment rate to just below 13 per cent, and a six percentage point decline in labour force participation to just below 58 per cent.

Essential and remote workers are less affected

To gain further insight into why some workers have been affected by the economic impacts of COVID-19 more than others, we also looked at the characteristics of different jobs.

We built four indices that capture whether workers in a given occupation are regularly exposed to infectious diseases, work in proximity to others, are considered essential workers or are more likely to work remotely. We constructed the indices from various sources, including O-NET OnLine, which gathers information on occupational tasks and adapted them to the Canadian Labour Force Survey.

Our estimates suggest that the labour market impact of the pandemic was significantly more severe for workers more exposed to disease and people that work alongside others, such as nurses and front-line workers. These workers were more likely to have COVID-19 related work absences, work fewer hours or leave the labour force. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we also found the effects are significantly less severe for essential workers and people who can work remotely.

Additionally, we find that these occupational differences interact with the inequalities noted above. For example, less educated workers are less likely to work from home and more likely to be essential workers. Women without kids are less likely to work from home, perhaps explaining why they were relatively harder hit by the economic shutdown.

Looking ahead

These results are important given the trade-off elected officials face when making decisions about reopening sections of the economy and preventing disease.

As policy-makers look to help displaced and affected workers, these findings highlight some of those most in need of assistance: the young, the unmarried and those with less education. Our results also suggest that governments should consider promoting policies that encourage businesses to let their employees work from home.

The federal and provincial governments have provided a variety of aid packages to individuals and organizations that should help alleviate financial burdens. A key concern going forward is that this aid could create a disincentive to work, especially among low-income earners. This could have the unintended consequences, increasing long-term income and wealth inequalities. All levels of governments should monitor this closely.