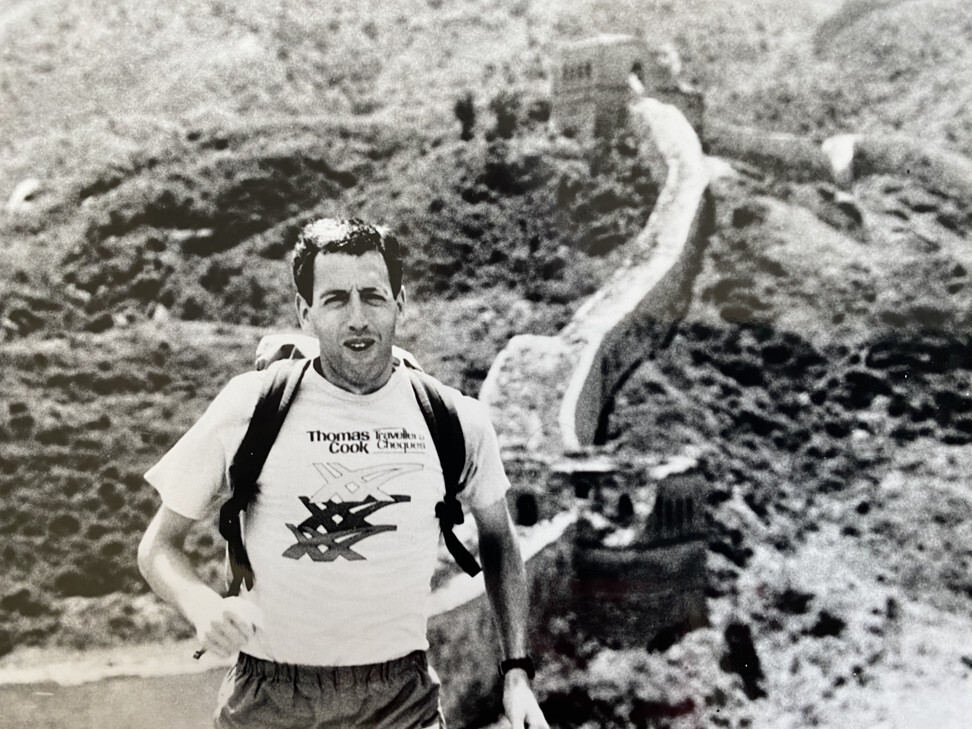

Briton William Lindesay, who has dedicated his life to preserving the Great Wall, in China.

- William Lindesay has run the length of the wall, documented its destruction and discovered a new dynasty of builders

- After three decades of wall-based research and adventures in China, he and his sons have turned their attention to Mongolia.

- Wall to wall: I was born in 1956, in Wallasey, England. If you take a ferry across the Mersey, as the song goes, you’re there. Significantly, the ferry goes past Liverpool’s Shanghai Bund-like waterfront to a place with “wall” in its name, so perhaps I was destined for China.I was schooled at St Aidan’s where the headmaster, Reverend J.P. Macmillan, or “Maccie” as he was known to us, maintained an unconventional approach to teaching. Every week we’d go on excursions, visiting churches, castles or farms. This engendered an appreciation of learning by experience – fieldwork, essentially.We were also taught subjects without boundaries: history, geography and science were fused into one, which has helped me take a multidisciplinary approach to understanding the Great Wall. Maccie always told us to have three books by our bedsides, a Bible, a prayer book and an atlas. I first saw the wall marked as a symbol in my bedside atlas. I must have been 11 when I told my class that I was going to China to see the Great Wall.Egyptian detour: After visiting the British Museum to see the Tutankhamen exhibition, in 1972, I got an early taste for Egyptology. At university in Liverpool, however, I chose to study geography and geology. I graduated in 1979 and managed to get a job in an oilfield in the Gulf of Suez. We did a 28 days on and off schedule.

Lindesay as a child with trophies won on a school sport’s day, in 1967. Photo: courtesy of William LindesayWhen the oil rig workers went home, I explored the monuments of Egypt, where I was eventually adopted by two American archaeologists. They loved what they did, whereas most of the oil rig workers hated their job. This made me imagine a life where I could do what I love and make a living.Run, Lindesay, run: One of my early passions was running. I used to clean up on sports day. My two brothers and I got caught up in the marathon fever of the mid-1980s. In 1984, my brother Nick suggested we go on a “real” cross-country run along Hadrian’s Wall (across northern England).We ran England’s Roman great wall from end to end over a long weekend. It was tough but a great experience. It was during a break that Nick suddenly said to me, “Hey Will, you should go to China and do the same on the Great Wall …” I had all but forgotten my boyhood dream. Why not, I thought? Mao was dead. Deng was opening up China. I had no loves or loans to hold me back.Try, try again: 1986 was a disaster. During my first attempt to run the Great Wall, I got lost, contracted dysentery and got a stress fracture in the foot. I was also arrested for trespassing in closed areas.In 1987, I returned to China for my second attempt and planned things better. I covered 2,470km of the route. It was a huge physical challenge as well as a protracted political battle: I was stopped by the police nine times for trespassing. In Shaanxi province, I was arrested twice in the same week in the same county. They deported me.

Lindesay as a child with trophies won on a school sport’s day, in 1967. Photo: courtesy of William LindesayWhen the oil rig workers went home, I explored the monuments of Egypt, where I was eventually adopted by two American archaeologists. They loved what they did, whereas most of the oil rig workers hated their job. This made me imagine a life where I could do what I love and make a living.Run, Lindesay, run: One of my early passions was running. I used to clean up on sports day. My two brothers and I got caught up in the marathon fever of the mid-1980s. In 1984, my brother Nick suggested we go on a “real” cross-country run along Hadrian’s Wall (across northern England).We ran England’s Roman great wall from end to end over a long weekend. It was tough but a great experience. It was during a break that Nick suddenly said to me, “Hey Will, you should go to China and do the same on the Great Wall …” I had all but forgotten my boyhood dream. Why not, I thought? Mao was dead. Deng was opening up China. I had no loves or loans to hold me back.Try, try again: 1986 was a disaster. During my first attempt to run the Great Wall, I got lost, contracted dysentery and got a stress fracture in the foot. I was also arrested for trespassing in closed areas.In 1987, I returned to China for my second attempt and planned things better. I covered 2,470km of the route. It was a huge physical challenge as well as a protracted political battle: I was stopped by the police nine times for trespassing. In Shaanxi province, I was arrested twice in the same week in the same county. They deported me. - I went to Hong Kong, changed my passport and returned. But a whirlwind romance kept me upbeat about China. In the course of being deported, I exchanged a few words with a girl in my hotel in Beijing. On my return, I knocked at her office door and invited her to dinner. It was love at first sight for me.

Lindesay and Wu Qi, in Xian, in 1992. Photo: courtesy William LindesayWu Qi refused my first proposal saying I was a foreigner and marrying was almost impossible. The second time, she said she liked me but her parents wouldn’t agree to it. The third time, she said, “Let’s try.” My achievements in 1987 – the first foot traverse of the wall by a foreigner and a cracking wife – were by the skin of my teeth. Wu Qi and I married in Xian in 1988 and my first book, Alone on the Great Wall, was published in 1989.Going wild: After a stint in the UK, we returned to China in 1990 and I took a job teaching in Xian. I retraced 1,200km of the epic sections of the Long March in 1990 and 1991, which resulted in my second book, Marching with Mao: A Biographical Journey (1993). But I yearned to get back to the wall.I eventually got a job at the China Daily in Beijing and bought a bicycle so I could visit the wall every weekend. Qi had our first son, Jimmy, in 1994, but I was spending so much time at the wall we were often apart. So in 1998 we bought a derelict farmhouse beside the wall and Qi organised local workers to do it up.We began our WildWall Weekends in 1999. When we had our second son, Tommy, in 2000, I thought it was high time I spent all my time doing what I loved – only things related to the Great Wall. I left my copy-editing job and WildWall Weekends became my full-time job.

Lindesay and Wu Qi, in Xian, in 1992. Photo: courtesy William LindesayWu Qi refused my first proposal saying I was a foreigner and marrying was almost impossible. The second time, she said she liked me but her parents wouldn’t agree to it. The third time, she said, “Let’s try.” My achievements in 1987 – the first foot traverse of the wall by a foreigner and a cracking wife – were by the skin of my teeth. Wu Qi and I married in Xian in 1988 and my first book, Alone on the Great Wall, was published in 1989.Going wild: After a stint in the UK, we returned to China in 1990 and I took a job teaching in Xian. I retraced 1,200km of the epic sections of the Long March in 1990 and 1991, which resulted in my second book, Marching with Mao: A Biographical Journey (1993). But I yearned to get back to the wall.I eventually got a job at the China Daily in Beijing and bought a bicycle so I could visit the wall every weekend. Qi had our first son, Jimmy, in 1994, but I was spending so much time at the wall we were often apart. So in 1998 we bought a derelict farmhouse beside the wall and Qi organised local workers to do it up.We began our WildWall Weekends in 1999. When we had our second son, Tommy, in 2000, I thought it was high time I spent all my time doing what I loved – only things related to the Great Wall. I left my copy-editing job and WildWall Weekends became my full-time job. Running on the Great Wall, in 1987. Photo: courtesy of William LindesayWall guard: Around the turn of the millennium,

Running on the Great Wall, in 1987. Photo: courtesy of William LindesayWall guard: Around the turn of the millennium,

. I called up the Great Wall Sheraton Hotel (in Beijing) to ask if they could sponsor a litter clean-up. We took 117 people to the Jinshanling section, including 10 journalists. The following week, the event hit the headlines.With the cuttings, I went to see Peng Changxin, director of the State Bureau of Cultural Relics. He told me there was no need for specific laws to protect the wall beyond the rebuilt tourist sites because most of it was inaccessible. I realised the Great Wall was an outdoor museum without a curator. I saw it as an historical landscape, transformed from defence to wilderness. I deemed its surroundings to be as important as its length.The wall had been built from materials sourced or made nearby. Villages close by were part of its cultural landscape – many had buildings made of Great Wall bricks. Villagers had valuable oral histories to tell. So I invented the term “Wilderness Wall”, which I abbreviated to Wild Wall in 1994 to highlight its plight, and differentiate it from the “tourist wall”, which was rebuilt and displayed the Unesco brass plaque. It was the wall that had been claimed by nature since its abandonment in 1644 I was intent on saving.The other William: William Geil traversed the wall (on horseback and foot) in 1908. Through his photos I realised Geil had seen a much more complete wall than I had in 1987. In 2003, I decided to spend a few weeks every spring and autumn looking for Geil’s locations and photographing them.What it showed me was often heartbreaking. Towers had been reduced to rubble, pristine “wallscapes” had been encroached upon by tacky developments. I became determined to ensure a better future by getting enough pictures together to show how the Great Wall had changed. I aimed to inspire its protection; to arouse the national consciousness. The Beijing government provided space for an exhibition at the Capital Museum in 2007.Flying the wall: In summer 2015, my sons, Jimmy and Tommy, asked for a drone. I’d always dreamed of seeing the wall from the air and their first flight convinced me flying should be the theme of our summer 2016 road trip along the wall to celebrate the 30th anniversary of my arrival in China.When I realised I’d be 60 that year I decided we would try to fit in all my favourite, mainly wild places, for 60 days. The footage was produced as a 90-minute package screened on BBC Four. People can hardly believe the documentary was the work of two lads, aged 21 and 16.Beyond heaven’s domain: I was aware my Great Wall studies had been one-sided, given that it is the product of a two-sided conflict between the nomadic northerners and the Chinese. Sometime around 2003, an old friend, Graham Taylor, brought me a gift from Mongolia: an atlas of Genghis Khan. I noticed a symbol named in the legend as the Wall of Genghis Khan. Lindesay and his youngest son, Tommy, practise archery near their Beijing home with traditional Mongolian bows. Photo: courtesy of William LindesayIn 2011, I was introduced to a Mongolian geographer who had seen Khan’s wall in the southern province of Omnogovi, and he agreed to lead me into the middle of the Gobi Desert. We found the wall near the border and had ministerial permission to research there.My findings, backed by radiocarbon dating, proved the wall there was built between 1040 and 1160, almost certainly by the Tangut people of the Xixia or Western Xia, a border regime that was attacked by Khan’s cavalry for 20 years, until his death in 1227. The Western Xia had not previously been considered a wall building dynasty but my findings provided convincing scientific evidence they built a wall to fend off Mongolian attacks.Two more expeditions to the Great Wall outside China followed, with my sons assisting me in the field, measuring, filming, droning and camping. We’ve all become quite taken with Mongolia, from archery to Mongolian “salad” (assorted offal). It has reshaped my understanding of the wall.

Lindesay and his youngest son, Tommy, practise archery near their Beijing home with traditional Mongolian bows. Photo: courtesy of William LindesayIn 2011, I was introduced to a Mongolian geographer who had seen Khan’s wall in the southern province of Omnogovi, and he agreed to lead me into the middle of the Gobi Desert. We found the wall near the border and had ministerial permission to research there.My findings, backed by radiocarbon dating, proved the wall there was built between 1040 and 1160, almost certainly by the Tangut people of the Xixia or Western Xia, a border regime that was attacked by Khan’s cavalry for 20 years, until his death in 1227. The Western Xia had not previously been considered a wall building dynasty but my findings provided convincing scientific evidence they built a wall to fend off Mongolian attacks.Two more expeditions to the Great Wall outside China followed, with my sons assisting me in the field, measuring, filming, droning and camping. We’ve all become quite taken with Mongolia, from archery to Mongolian “salad” (assorted offal). It has reshaped my understanding of the wall.