New Straits times fired off two pieces in the past few days, again stirring the situation in bilateral relations between Malaysia and Singapore. First, the newspaper published a report from a talk about the water deals binding both countries, organized at University Kebangsaan Malaysia and then followed up with a leader next day, which was an all-out anti-Singapore offensive, blaming the city-state for stonewalling the requests for a price review and damaging relations between the two countries.

Anybody who wrote this has got some cheek, so let’s remind the ignorant and reckless author of that hit piece about a few facts.

Singapore Has Always Been Willing to Talk

Let’s deal with the most frequently repeated accusation – that Singapore doesn’t want to discuss the water deals. Well, perhaps this selective amnesia explains why the country is so poorly managed, if people in charge of it forget very simple facts from not so distant past.

Firstly, Singapore has another water agreement that it signed in 1990 – which is a supplement to the deal that expires in 2061 – and led to the construction of Linggiu Dam in Johor, benefiting people on both sides of the border. Under this agreement Singapore pays for the water it purchased in accordance to a formula rather than fixed price.

Secondly, both countries already sat down to negotiate new conditions of water supply from Malaysia mere 20 years ago. In the aftermath of the 1997 crisis, when it looked like Malaysia may be needing financial support, neighbors entered negotiations over a number of different issues – including the price of water supplied to Singapore.

Over subsequent five years, between 1998 and 2003 Mahathir and his administration kept changing its demands – raising prices, firing off hostile comments, making and retracting controversial statements about the two countries – anything but constructive negotiation.

Malaysian proposals for the new price were quite random – starting at 30 sen and reaching over 6RM per 1000 gallons at one point (over 200 fold increase).

All this time Singapore has not only agreed to certain proposals (at 30 or 45 sen – which would be 10x to 15x higher than the current price) but was also willing to bear the costs of infrastructural investment in Malaysia to further enhance the water supply – water, let’s remember, that otherwise is freely discharged into the sea.

It was due to incessant Malaysian uncooperativeness – time-wasting that lasted five years – that the talks had ultimately broken down and no amendments to the deals were made.

All that Singapore wanted is to extend guarantees of supply beyond current agreements. It agreed to higher prices, it offered investments that would increase water output in Johor (today badly needed in the state which faces water shortages) but Malaysia was clearly not interested in any deal, changing its conditions from one meeting of the two parties to another – until there was no reason to meet again.

To accuse Singapore of unwillingness to discuss, review or change the conditions of the water deals is a Goebbelsian lie.

What, incidentally, shows how low journalistic standards are in NST.

Malaysia is Not Seeking Discussion But Extortion

I have to say I burst out laughing when I read the following quote by the “international law expert”, Associate Professor Salawati Mat Basir:

“What bothers me more is the lack sense of gratitude from our neighbour for all that Malaysia has done for them.” / SALAWATI MAT BASIR

And it’s not an isolated opinion – you keep hearing it all the time, how Singapore should be grateful for what Malaysia is providing it or that somehow without Malaysia the city would not exist or be so successful.

A-ha-ha-ha!

Let’s get something straight – Singapore is independent because it was KICKED OUT of the federation and the water deals were signed to make sure it can stay out.

The reason was rooted in borderline racist attempts to ensure Malay dominance over the multi-ethnic society – which so far has only produced a corrupt ruling class and widespread cronyism, in a country that started the 1980s on par with South Korea. We can all see where both countries are today.

In subsequent decades Singapore had borne the cost of building, maintaining and expanding infrastructure that allowed it to draw water which would freely flow into the sea. Ironically, through that it helped Johor to secure greater supply for itself – in the general absence of interest of Malaysian authorities, whose negligence has led the country on the brink of acute water shortages – and sometimes beyond it, like in 1998 or more recently in 2014 (which I experienced myself in KL at the time).

If anybody it’s the millions of Malaysians in the south of the country who have a lot to be grateful for to Singapore, which has provided what their own politicians have failed to provide – and even supplies Johor with cheap, treated water that the local authorities sell to Malaysians at a significant profit.

Most of the country is so badly and incompetently managed that despite lying on the equator and being generously watered down from the skies, it still struggles to secure sufficient water supply – not to mention quality, since drinking from the tap anywhere in Malaysia is generally not advisable.

But the statement about how Singapore should somehow be grateful to Malaysia is doubly egregious when you consider what Mahathir’s government has done to its neighbor in the past two years:

Violated territorial waters of the city-state.

Paralyzed Seletar airport’s operations after ILS system was installed to enhance safety – mainly of Malaysian airlines.

Launched a dispute over airspace control, even though it’s been arranged so that Changi airport can continue safe operations.

Froze the High-Speed Rail link project in breach of earlier agreements.

Keeps delaying and throws new obstacles against the RTS mass transit link to Johor.

Went as far as to restrict exports of food ahead of the Chinese New Year in 2019.

Oh yeah, and revived the idiotic “crooked bridge” idea – that would cost billions, even as its leaders go around crying how the country so, so poor right now <sob>.

As I wrote last year, under new government Malaysia engaged in “parang diplomacy”, behaving like a thug, trying to bully it’s diminutive neighbor.

And its representatives have the cheek to talk about gratitude.

With such a tone how can anybody treat Malaysian requests for a review of the water deals seriously?

Of course there’s a better reason to ignore them – because Malaysia doesn’t want them either. Just like 20 years ago when Mahathir had a good chance to increase the price by 10 or maybe even 20 times – but was so uncooperative that the talks broke down.

It’s not about the money, it’s not about water, it’s about spiting Singapore.

Regardless of how you interpret what the agreement stipulates – i.e. whether the agreement allowed for a review only in 1987 or simply at any time beyond it, it still requires both sides to agree. And can you blame Singapore for its reluctance given its past experiences? Last time it wasted five long years on a Malaysian wayang – and now the person who led it then is back in power. What can the outcome really be?

Singapore does not want to negotiate not because it doesn’t see value in it or that such a deal could not be beneficial to both sides – but because Malaysian behavior is totally unacceptable and its leadership is entirely untrustworthy.

And, given its current performance, even Malaysians themselves would agree with this judgment. So how can anybody expect a foreign country to trust the authorities that even the locals don’t?

I’m pretty sure Singapore would be happy to negotiate new water deals with Malaysia. After all, even with its stated goal of self-sufficiency, it simply makes economic and political sense to keep other options – especially as cheap as drawing low-cost water from a river nearby – open.

It also makes sense for two neighbors – both dwarfed by far more populous countries in the ASEAN and by rising China – to cooperate rather than fight. Unfortunately, none of it is going to happen until Malaysia can defeat its insecurities.

The core of the problem is that Malaysian leaders have an acute inferiority complex.

After the split in 1965 they and their predecessors have inherited a fairly large, fertile country, abundant in natural resources (metals, forests, oil), rich fauna and flora and millions of people – and yet they were left behind by little Singapore that had nothing.

Malaysia is like a big brother who kicked his smaller sibling out of the house, keeping the family wealth to himself – and then proceeded to squander it, while the youngster has become far richer and more successful on his own. And now the culprit is back claiming the victimized relative owes him something. Fortunately, however, the tables have already turned.

Mahathir had over 20 years to negotiate new or renegotiate old water deals. And Singapore has always been willing – in the 80s, in the 90s and early 2000s. 1987 deadline lapsed, Linggiu dam was built, five years were wasted before the old fox stepped down in 2003. Today he’s back and so is his rhetoric, that is not going to bring any progress.

So, if Malaysia genuinely wants to talk, it has to speak in a different language, come up with a good offer and be willing to see it through.

None of it is likely to happen under current leadership, however. So, as I wrote in late 2018, before there’s any chance for progress, Mahathir must step down.

Monday, April 13, 2020

We Need to Stop Trying to Replicate the Life We Had Attempting to translate your old social habits to Zoom or FaceTime is like going vegetarian and proceeding to glumly eat a diet of just tofurkey. By ASHLEY FETTERS

The best part of any social gathering is the haphazard array of smaller, more intimate gatherings into which it inevitably breaks down. Just ask Shakespeare, or F. Scott Fitzgerald, or Edith Wharton. Romeo and Juliet meet during a stolen moment in the middle of a masquerade ball. Nick Carraway inadvertently befriends Jay Gatsby at a party when he’s off to the side, gossiping about Gatsby. The love affair between Newland Archer and Countess Ellen Olenska begins when the pair share a private giggle during a dinner, just out of earshot of the other guests.

I’ve been thinking wistfully about side conversations a lot the past few weeks. Like many others who are sheltering in place to curb the spread of COVID-19, I’ve participated in a number of Zoom happy hours of late. As friends trickle into the videoconference, one by one they demand to know how the friend who lives abroad is doing, you know, under the circumstances; how the friend whose wedding has been postponed is doing, how the friend who works in a hospital is doing. Each of the aforementioned friends then has to respond, while those of us who have been on the call from the start hear their responses for a second, third, fourth time. Eventually, lagging internet connections and the subsequent chaos of people talking simultaneously (“Sorry, you go!” “No, you go!”) force us all into a weird pattern of monologuing one after another. At this point, I always find myself desperately wishing I could discreetly ask another participant to “go get a refill,” or subtly invite them to break away and catch up in a quieter and less chaotic conversation of our own. (Sure, we could start a side chat on another platform or text each other, but it’s not the same.)

Some three or four weeks into virtual social interactions being essentially the only social interactions outside the home for most people, many of us have tried to go about our usual rituals, just online—and found the results a little underwhelming. The life we live now is not conducive to birthday dinners or bar flirtations or run-ins with friends who live down the block. It is small, slow, intimate; every encounter requires planning ahead. Of course trying to jam the happy, sprawling commotion of a night out into a row of little boxes on a laptop screen (itself jammed into the little box that is your home) is jarring. So it seems time to abandon efforts to replicate our old social life in online spaces—and instead adapt our interactions to our new normal. What if, instead, we leaned into the smallness, the slowness, the intimacy? What would our social life look like then?

Obviously, some aspects of prepandemic life can’t be re-created or replaced. In person, humans can sync up to one another through gaze and body language—which is impossible over phone or text, and difficult over video chat. Melissa Mazmanian, an associate informatics professor at UC Irvine, recently had to switch from in-person to Zoom interviews for a research project, “and some of them just don’t work as well,” she said. “I can’t read [subjects’] body language and help them feel comfortable in the way that I can when I’m there.” Nicole Ellison, who teaches at the School of Information at the University of Michigan, noted to me that in addition to messing with body-language clues, many teleconference hangouts require a lot of planning—which can throw off the vibe for friends who otherwise usually hang out on a spur-of-the-moment basis.

But perhaps most important, videochat happy hours fail to measure up to real-life happy hours because we keep comparing them with real-life happy hours, expecting that they will satisfy the same desire with the same efficacy. I told Ellison I found it annoying that I sometimes feel like I need to raise my hand before speaking while I drink beers remotely with my friends, and she replied that this was probably annoying only because I’d imported the expectation of not having to raise my hand from meatspace. Trying to translate your old social habits to Zoom or FaceTime is like going vegetarian and proceeding to glumly eat a diet of just tofurkey, rather than cooking varied, creative, and flavorful meals with fruits and vegetables. The challenge, then, of adapting to an all-virtual social life may lie in reorienting our interactions around the strengths of the platforms where we can be together.

It’s no small task to fully reinvent social life itself from your home, but with any luck, the new ways of spending time together that people discover will succeed in making this period of isolation a little less isolating. Of course, a satisfying all-virtual social life will look different for everyone. For some, this time will present an opportunity to put more thought and energy into individual relationships and deep one-on-one conversations, which translate well to platforms like Zoom or FaceTime. Others who find themselves longing for a friend-group hang or a team dinner might have to get a little more creative.

Some activities groups of friends did together before quarantine are easy to replicate on virtual formats. For example, Ellison told me that her book-club meetings, during which participants are used to taking turns speaking, have translated quite naturally to Zoom. (My own much less dignified version: I recently discovered that certain drinking games I used to play with my college friends—especially those involving a deck of cards that’s handled by only one dealer—can be played perfectly well over videochat.)

Some people have already devised new, surprising ways to enjoy one another’s company remotely with the tools at hand. I was recently invited to participate in a virtual reading of Shakespeare, for example, by some friends who weren’t previously in the habit of getting together to read classic plays. My colleague Julie Beck wrote about a group of friends who hosted a PowerPoint party, in which they took turns presenting amusing (or amusingly self-serious) slide presentations on topics of their choice. For that kind of event, Zoom’s screen-share feature handily facilitates an activity that might actually be harder to pull off in the physical world. Meanwhile, the browser extension Netflix Party—which lets friends sync up movies and TV on Netflix and chat as they watch—saw a surge in search-engine interest in late March, around the time that many shelter-in-place protocols went into effect. Ellison predicted we may soon see people inventing ways to signal that they’re up for an aimless break-room- or bar-style chat, perhaps by signing in to a teleconferencing app, sharing the link with friends, and seeing who pops in.

The runaway success of the online Nintendo Switch game Animal Crossing also speaks to the appeal of unfamiliar virtual spaces. In Animal Crossing, players can interact with other online players rather than just the characters created by the game, and players who are friends in the physical world can link up in the game and host one another virtually on their “islands.” Crucially, in spaces like this, the norms and communication patterns of face-to-face interaction don’t exist. “We’re not necessarily expecting [a setting like Animal Crossing] to be the real world, and maybe that’s partly why it works,” Ellison said. She added that she wouldn’t be surprised if virtual-reality experiences also become more popular for much the same reason: They can offer people the ability to roam around and interact in unstructured ways, but with just enough novelty to avoid unfavorable comparisons with face-to-face interactions.

Much of what’s clunky and grating about Zoom happy hours and their ilk is that many people use the still-unfamiliar tech in clunky, grating ways. A lot of Ellison’s friends, she told me, are technology researchers—so they’ve had more exposure to teleconferencing than a good chunk of the population, and know without being told to mute themselves when someone else is talking, and to sit with the light in front of them to avoid showing up on-screen as a spooky silhouette. She expects that most people who have just recently migrated their work to teleconferencing will catch on to subtle, unspoken rules like these pretty quickly: “Norms and practices will evolve over time,” she said. “I promise you—we’ll get better at it.”

I can’t in good faith suggest that hanging out remotely will be an adequate replacement for time spent physically together, even if and when we develop better virtual social skills. Even those of us who succeed in adapting our social life to platforms like FaceTime will still undoubtedly long for the delicious, crackling chemistry of actual face time. But in this moment, it’s worth remembering that the options we have can be nourishing, too—and even satisfying, if we get creative enough. I suspect we’ll figure that out when we stop trying to pretend the tofurkey tastes just as good.

The Pandemic Exposes India’s Apathy Toward Migrant Workers More than half a million people have left India’s cities since the lockdown was announced. By Patralekha Chatterjee

The defining images of India’s three-week lockdown may be of migrant workers, with bags perched on their heads and children in their arms, walking down highways in a desperate attempt to return to their villages hundreds of miles away.

India, a country of more than 1.3 billion people, is not among the worst affected by the pandemic. Not yet, anyway. The total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases has crossed 7,000, with more than 200 deaths.

But the virus is exposing once again India’s deep economic divide, and the government’s apathy toward the workers who power the country’s growth.

In the middle-class South Delhi neighborhood where I live, we’re preoccupied with inconvenience. No one likes to be cooped up at home for days on end. No eating out, no visiting one another; masks must be worn when you go to the grocer or the bakery. With few cars on the road, some of my neighbors have noted one silver lining: The sky is clear and blue, something we rarely see in one of the most polluted cities in the world.

A few miles away, in parts of the Indian capital where many migrant workers live, the lockdown is more than an inconvenience.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi ordered the lockdown with less than four hours’ notice. “Forget what it is like stepping out of the house for 21 days. Stay at home and only stay at home,” he said. He mentioned nothing specific about the daily-wage earners—mostly migrant workers—whose income, in an instant, disappeared.

Migrant laborers are among the most vulnerable parts of the “informal sector,” which make up 80 percent of India’s workforce. The country’s infrastructure is built on the backs of these workers. They construct malls, multiplexes, hospitals, apartment blocks, hotels. They work as factory hands, delivery boys, loaders, cooks, painters, rickshaw pullers. They stand the whole day by the side of the road selling fruits and vegetables and tea and flowers.

They often come to cities to look for work, because they cannot make a living in their village. They are rarely part of a trade union and typically work without any contract or benefits. Most earn cash, and do not leave a paper trail. They are also disproportionately from historically marginalized groups, referred to, in the country’s official lexicon, as “scheduled castes” (those at the bottom of Hinduism’s hierarchy of castes) and tribal groups. Nationally, these two groups make up about 25 percent of the population. India’s constitution, adopted in 1950, guarantees them equality of opportunity, reserved positions in educational institutions, government jobs, seats in Parliament and in the state assemblies. In practice, however, they often face discrimination and prejudice.

The night Modi instituted the lockdown, migrant workers started leaving Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Chennai, Kolkata, and just about every other city to which the economic opportunities had drawn them in the first place. They knew they could not afford to stay in the city if they had no income. In their village, they had family, wouldn’t have to pay rent, and were more likely to get something to eat. All buses, trains, and taxis had been stopped, so they had no transportation. News reports said workers were stranded in railway stations. Some tried to surreptitiously flee in container trucks carrying essential commodities, but they were intercepted.

So the people started walking, first in a trickle and then in a flood. By the next evening, a shocked nation saw images of thousands walking down highways. More than half a million people have left India’s cities. At least 20 have died while trying to make it home.

This mass movement surprised authorities. Clearly, no policy maker had planned for such a reaction, and no detailed contingency plans seemed to be in place. Officials issued frantic orders to seal interstate borders and for people to maintain their distance from others so that the virus could not spread. They said that those on the move should quarantine for 14 days. Yet how could they?

The government asked voluntary organizations to help, and when soup kitchens and shelters were set up, they were soon packed with people. A few state governments provided buses for the migrant workers, but so many needed a ride that the lines were half a mile long.

Migrant workers never seem to be much of a consideration for politicians. This episode is only one of many examples of that fact. These workers, despite their numbers, have no political clout. Many are registered to vote in their village. But when election day comes, they are usually in the city where they work and unable to cast a ballot.

Statistically, they are almost invisible. Because they consistently move between villages and cities, and among work sites, capturing their number is difficult. The federal government’s 2017 economic survey said, “If the share of migrants in the workforce is estimated to be even 20 percent, the size of the migrant workforce can be estimated to be over 100 million.”

India has welfare measures for people below the poverty line, but migrant workers rarely have access to them. Chinmay Tumbe, a professor at the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad and the author of India Moving: A History of Migration, points out that welfare services are often only available in one’s place of birth.

Partha Mukhopadhyay and Mukta Naik, who work for the Centre for Policy Research, one of India’s leading think tanks, wrote in a commentary piece in The Indian Express:

Field studies have consistently claimed short-term labour mobility in India was significant. The past week has seen emphatic validation of these claims as highways across the country have been pedestrianised. In its callous haste, the Union government, when it announced the lockdown, did not think through how migrants, caught unawares, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, would respond. Now they know.

A lockdown, however necessary, was always going to be unbearably difficult for those without a social and economic cushion. And now some states are opting to extend the quarantine. On Friday, some migrant workers in western India protested in the streets as they demanded a salary and approval to return to their villages. This crisis will only worsen as they alternate between the fear of catching the virus and the fear of zero income. Sanjoy Mondol, a 22 year-old Bengali migrant construction worker, now in a shelter in the outskirts of Gaya, in Bihar, eastern India, told me over a crackling telephone line that his elderly parents call him several times a day to find out how he is doing. His young wife is expecting a baby. "We are being fed. But I have no work and have run out of money,” he said. “I can't even send any money home. Somehow, if I could get back to my village in Bengal, I would be happy. I could do some small thing, maybe sell vegetables. Be with my wife, my parents. I can't bear to hear them weep, each time they call me. Please get me home."

Meanwhile, India’s winter crop is ready for harvest, but farmers cannot find laborers to take it to market. Essential supplies are finally reaching city warehouses, but there is no one to unload the trucks. The migrant workers cannot get back to work, because there is no public transport.

No one really knows whether COVID-19 has entered the rural parts of the country where nearly 70 percent of Indians live. There are reports of neighbors shunning migrants once they arrive home, because they fear they carry the virus. And a shocking photo surfaced of migrant workers and their children in a small town being sprayed with bleach meant to sanitize buses.

For the workers who stayed in the cities, the same uncertainty exists. Shashi Rani, who came to Delhi to find employment, has not gone back to her village. She still sells garlands in front of my neighborhood temple. The temple is under lockdown; a few devout people bought flowers from her for the recent Hindu religious festival Navratri. Otherwise, she has hardly any customers. She worries about how she will sustain herself. The Delhi government’s mobile food vans offer some help. But she does not think the owner of the shanty where she lives will agree to defer her rent, despite a government directive to that effect.

The local governments in Delhi and in some other states have set up shelters for migrant workers who can’t work and could not get back home. Nonprofits are also trying to help. But India is a patchwork quilt; not every state is equally equipped.

Jan Sahas, an Indian nonprofit, recently conducted a survey, “Voices of the Invisible Citizens,” about the impact of the lockdown on migrant workers. They interviewed 3,196 migrant construction workers from northern and central India. The results paint a dismal picture: “62 percent of workers did not have any information about emergency welfare measures provided by the government and 37 percent did not know how to access the existing schemes.”

The new coronavirus has given migrants a sudden visibility in the national discourse. But the acuteness of their plight today is a result of the fact that India ignored them during normal times.

The Timeless Lessons of Easter Are More Timely Than Ever This year, Passover and Holy Week overlap, and the lessons of the two holidays apply to both believers and unbelievers alike. By Philip Yancey

On wednesday and Thursday nights, when Jews gathered in some virtual way for the seder feast, they asked, “How is this night different from all other nights?” Christians would do well to reflect similarly. The Jewish celebration of Passover and the Christian celebration of Holy Week overlap this year. Both recall dark nights from long ago when desperate people of faith gathered to face a scary future. Both, however, are now overshadowed by a global threat from a virus that respects neither religion nor geography. What lessons might we take away today, under this very different threat?

Passover commemorates a time when not one but 10 plagues were unleashed, on a nation that had enslaved the Israelites. According to the Book of Exodus, God said, “I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt … So I have come down to rescue them.” Thus began a power contest between Moses’s God and the Egyptians’ many gods. The plagues culminated in a final affliction that would take the lives of every firstborn son in Egypt.

On that night of blood and death, the Israelites huddled in their homes, listening to the loud sounds of grief but protected by the marks on their doorposts that caused the plague to “pass over” their own homes. After more divine intervention, the Israelites escaped at last and began their march to the promised land. That image, of slaves walking free, has inspired liberation movements throughout history, most notably the American civil-rights movement.

Over the next 40 years, God acted as a kind of divine nanny, directing the group’s every move, supplying food and water, dispensing the Ten Commandments. Yet, rather than expressing gratitude, the Israelites responded like spoiled children, by grumbling and plotting insurrections. Instead of cooperating as a true community, they soon splintered into factions, blaming their leaders and demanding more miracles. The Israelites finally made it to the promised land, although a journey that should have taken a few weeks dragged on for four decades, as God waited for the generation of complainers and rule-breakers to die out.

Passover celebrates that first night of liberation, when courage overcame fear and beleaguered people joined together in unity—a good thing to remember in a year when a virus forces social isolation. “There’s no way to replace having Passover with your parents, your grandparents, your friends and loved ones,” Rabbi Yaacov Behrman from Brooklyn told a journalist recently. Shelter-in-place orders will keep seders in 2020 from being inclusive group events. Yet, he added, “these prayers are what unite us, right now and through many generations. The times we are living in will bring these prayers alive while we reflect on what is happening all around us.”

riters of the gospels portray Jesus as recapitulating the experience of his forebears, including a flight to Egypt and a 40-day temptation in the wilderness. Some compatriots welcomed him as a leader like Moses, one who could deliver them from another oppressive regime, the Roman empire. Instead, of course, he met an early death.

All four Gospels set Jesus’s crucifixion during Passover in Jerusalem—yet another historical echo—and all four record a final meal with the disciples. In John’s detailed account, Jesus spells out his own fate that awaits him, though his followers seem uncomprehending. He is turning the mission over to them. “As I have loved you, so you must love one another,” he says. To underscore the point, he takes on the role of a servant and, despite their protests, washes their feet.

Then comes Easter Sunday, the day that changes everything—eventually. With surprising transparency, the Gospels record that initially the disciples refused to believe the rumors of resurrection. Unlike scheming conspirators, or gullible simpletons, they reacted as any rational person would: with incredulity. Dead bodies in a sealed tomb don’t suddenly reappear, alive, a few days later. One by one, Jesus convinced the disciples otherwise.

As if in a daze, some of them headed home, to resume their old profession of fishing. And when they saw Jesus one last time, they asked if he was now planning to restore the kingdom to Israel. They were still unable to grasp what he had told them, that his death would inaugurate a new kind of kingdom, not tribal or ethnic, but one without borders, a spiritual kingdom that would spread to the outermost parts of the Earth.

Seven weeks passed between Easter and Pentecost, when the disciples finally understood their mission. Suddenly, “with a sound like the blowing of a violent wind,” the spirit of God descended, transforming the cowering disciples into bold and courageous messengers. The kingdom had come, though not just to Israelites: to Parthians, Medes, Romans, Cretans, Arabs, and many others, as the Book of Acts details.

“The kingdom of God is within you,” Jesus had told them, a concept they comprehended at last.

Jews and christians share the belief that humans are God’s image-bearers, with the mission of mirroring God’s own qualities of mercy, compassion, and steadfast love. At Passover, Jews relive a time when they were slaves, a reminder to care for the needy and disenfranchised. They are encouraged to invite the less fortunate and those who live alone to the seder feast, a tradition made impossible this year by coronavirus restrictions.

For Christians, Holy Week focuses on a God-man who makes a willing sacrifice and then charges others with emulating his example of selfless love. Against all odds, in the three centuries after Jesus’s death, Christianity grew from a tiny subset of Judaism to become the official religion of the Roman empire. The sociologist Rodney Stark argues that Christians’ response to suffering helped fuel the expansion of the faith. When diseases such as smallpox and the bubonic plague hit Roman villages and the locals fled, Christians stayed behind to nurse not only their own families but also those of their pagan neighbors. When Romans abandoned their unwanted babies by the roadside, Christians adopted them.

After Christians became a majority in Rome and all of Europe, however, a kind of amnesia set in about Jesus’s message of nonviolence. Under Christendom, some of Jesus’s followers became persecutors rather than the persecuted, and waged wars of religion in the name of the “Prince of Peace.” Tragically, their spiritual ancestors, the Jews, made an easy target.

The lessons of Passover and Holy Week apply to believers and unbelievers alike, as a tiny virus has humbled us all. When we gather digitally in search of human contact, we do so with a new understanding of how vulnerably connected we are; the novel coronavirus that has spread around the world provides the proof. We will defeat the malady only by putting aside our divisions and working together as a global community, united against a common threat. Real victories are won not with the sword, but through service and care for one another.

The governor of Colorado, where I live, gives regular updates on the COVID-19 outbreak, in press conferences marked by honesty and good sense. Jared Polis is the first Jew to hold the title, and I was recently surprised to hear him quote a passage from the New Testament, 1 Corinthians 13. “And now these three remain,” said the governor, “faith, hope and love.” He described the faith we have in the scientists working on vaccines and cures, and in the health-care workers tending the sick. Next he reported on some reasons for hope, as social distancing finally shows results in our state.

“But the greatest of these is love,” he concluded. A challenge like COVID-19 can be met only if we all join together in a display of willing sacrifice and selfless love. Something worth pondering in a year when Passover and Holy Week overlap.

Boris Johnson Can Remake Britain Like Few Before Him The British prime minister, released from the hospital today, needs to show he’s more than just a feel-good story. by TOM MCTAGUE

Just as Britain braced for the most crucial weeks of this great struggle, its commander was taken from the field. Boris Johnson, relentless climber of life’s knotty ladder, had been dragged from the top at the very moment it mattered most, like in a Greek tragedy, and somehow fitting for this strangely antiquated figure. For a moment, there was serious concern that the country was about to lose its most consequential prime minister since Margaret Thatcher, the man who had remade the country in his image, first by convincing it to vote for Brexit and then by ensuring it was not lost in the wreckage of his predecessor’s failing government.

The real story proved more prosaic. Protected by modern medicine, Johnson was able to recuperate from COVID-19, eventually moved out of the intensive-care unit, and was today released from the hospital a week after he was admitted. Still, this story—one not tied to some kind of fated tragedy or test of personal virility—is revealing.

Johnson’s illness touched on something unique about him and his hold on Britain that, for good or bad, has come to define both. In falling ill, Johnson came to embody the national struggle against the coronavirus, just as he had come to represent Brexit in 2016, and, before that, as London’s mayor, the 2012 Olympic Games. In his recovery there is something symbolic too—even as Britain grapples with hundreds of deaths a day from COVID-19 to rank among the worst-hit countries anywhere in the world, his tale offers some hope and optimism.

Johnson rejoins a government that made little sense without him—it was and is his. Not even Tony Blair, forced to cohabit with Gordon Brown, was quite as dominant. Johnson’s government is a court, in which he is the king. Its revolutionary nature, taking Britain out of the EU, has already remade Britain. Now, though, he is able to return to the fray with the unique power to change the country all over again—and with it, his own legacy. Johnson has been given a second act, even before the first one was complete.

Brexit requires refashioning Britain’s relationship with Europe. But the extraordinary nature of the coronavirus crisis, its reach into every aspect of life, means that the country’s economy, state apparatus, and social mores need rebuilding as well. Johnson gets to lead this reconstruction.

Public sympathy and support for Johnson will, of course, wilt as he returns to work and begins to make the difficult decisions necessary to contain this crisis, get the economy back on track, negotiate Britain’s future relationship with the EU, and balance the books. The inevitable public inquiry into the current crisis, and Johnson’s handling of it, is unlikely to spare him and his advisers criticism. Britain’s performance to date looks to be somewhere between average and distinctly unimpressive, if not far worse. Yet, perhaps aided by his illness—though evident before that—Johnson has maintained the strong support of the public. At heart, he is not generally seen as a malevolent figure, but rather as a far-too-human actor, unable to take necessary steps quickly enough because he is not serious enough. In truth, Johnson’s political weaponry—his optimism and energy—proved ill-suited to the opening stages of the coronavirus challenge.

For the post-pandemic rebuild, however, that weaponry may prove far more effective, as Britain requires reenergizing. For all the war rhetoric and metaphors, Johnson is a peacetime leader. His success has been built on risk-taking, impulse, and making people feel better. These traits will come in handy. He will, of course, also need a plan, a vision of Johnsonism to show that he offers more than feel-good Berlusconismo. He needs to develop an idea of what the country will look like in 2024, the year of the next British general election.

In her address to the nation earlier this month, the Queen noted that while the national lockdown might be hard, it provided “an opportunity to slow down, pause, and reflect.” Reflecting on Johnson’s legacy, it is clear that, had he succumbed to the coronavirus, he would already have ranked among the most consequential politicians in postwar Britain. Brexit alone meant Johnson achieved more of lasting consequence than any leader other than Clement Attlee, who introduced the social-democratic postwar order, and Thatcher, who tore it down.

Johnson helped set the tone of British euro skepticism as a journalist, gave it moderate respectability as a politician, and then played an instrumental role, if not the instrumental role, in its eventual triumph. He has come to dominate our national life here in Britain. He is loved and loathed, a source of fun and fury, but he is everywhere, and always Boris, the clown who cannot be contained or stopped, whose rise to the pinnacle of British life was somehow inevitable.

It is perhaps for these reasons that the news of Johnson’s sudden deterioration came as such a jolt to so many, unnerving even those implacably opposed to him. The feeling seemed to be: If COVID-19 can lay Johnson low, what about me? I received messages from old friends I’d assumed to be hostile asking about his condition. Johnson’s lightness, his positivity, seemed to be missing. Maybe his relentlessly positive outlook contributed to the scale of the crisis, perhaps not, but there was a feeling that at least he offered some kind of hope.

The response to his hospitalization pointed to his national appeal. Does he allow people to pretend everything will be okay? To take the risks they want, to behave irresponsibly or irrationally? Robbed of the reassurance he offered, did the country panic just a little bit? With Brexit, he rejected the “doomsters and the gloomsters” and convinced people—once during the referendum, and again in December’s general election—to take a leap into the unknown. This time, his tentative leadership and reluctance to impose tougher restrictions look to have made the crisis worse, but his poll ratings nevertheless jumped.

What has always been so curious in writing about Johnson is the sense of destiny that has attached itself to him through his life. From the moment I can remember Johnson bursting into the public consciousness on Have I Got News for You, Britain’s biggest TV political-satire show, his future rise was a matter of national discussion. That he would one day become prime minister was commonly accepted. Yet there was always a darker side to the speculation—that upon reaching the top, he would either burn bright or explode in public view, perhaps both. Even his family and friends were concerned that his premiership would be a disaster.

Most of those I spoke with before he became prime minister thought Brexit would be this disaster, yet his term has been marked by extraordinary success, politically at least. This was a man who constantly flirted with danger, who indeed appeared to be drawn to it, but who—until the coronavirus crisis—was barely touched by it.

The pandemic may yet prove to be this calamity. Perhaps history or the electorate will judge him for not taking it seriously enough, for acting too slowly or too reluctantly. At first, there had been a glint in his eye, a smirking irony in his repetition of the government’s hand-washing message. Then when the news emerged that he’d contracted the virus, it seemed little more than an inconvenience with a whiff of farce thrown in, even as most of the country were experiencing the national lockdown. How had the prime minister, his chief medical officer, and his health secretary allowed themselves to be infected at the same time? Was it indicative of his lack of seriousness—and the country’s? There was even comedy about this moment too, reflected in the memes and jokes circulating on the nation’s phones. His sudden deterioration came just as things in the country at large were getting worse. Johnson had not been laid low saving the day like Horatio Nelson, leading Britain through its modern-day Battle of Trafalgar. Instead, he appeared to be living the crisis itself.

In a profile of Johnson I wrote last year to mark the culmination of his life’s ambition, to become Conservative Party leader and prime minister, I explored the perception of destiny that has clung to him, the source of his burning ambition, and the risk of self-destruction many of those around him have always perceived. The profile closed with the obituary written by the Roman poet Ovid of Phaeton, the tragic child of the sun: “Here Phaeton lies; he who sought to drive the chariot of his father, the sun; if he did not succeed at least he died daring great things.” This was Johnson’s mission—to do things, even at great risk. He now has his chance all over again.

How China Deceived the WHO U.S. senators are calling for investigations and the president is threatening to cut off funding. What happened? By KATHY GILSINAN

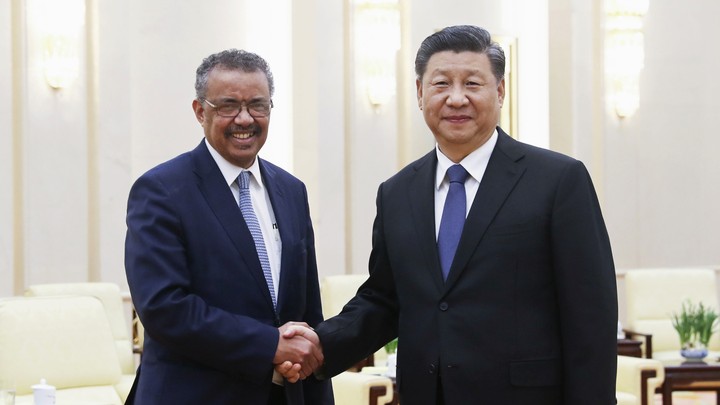

In January, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus met with China's Xi Jinping and praised his response to containing the coronavirus—even after China allowed it to spread unchecked in its crucial early stages.

Back in January, when the pandemic now consuming the world was still gathering force, a Berkeley research scientist named Xiao Qiang was monitoring China’s official statements about a new coronavirus then spreading through Wuhan and noticed something disturbing. Statements made by the World Health Organization, the international body that advises the world on handling health crises, often echoed China’s messages. “Particularly at the beginning, it was shocking when I again and again saw WHO’s [director-general], when he spoke to the press … almost directly quoting what I read on the Chinese government’s statements,” he told me.

The most notorious example came in the form of a single tweet from the WHO account on January 14: “Preliminary investigations conducted by the Chinese authorities have found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel #coronavirus.” That same day, the Wuhan Health Commission’s public bulletin declared, “We have not found proof for human-to-human transmission.” But by that point even the Chinese government was offering caveats not included in the WHO tweet. “The possibility of limited human-to-human transmission cannot be excluded,” the bulletin said, “but the risk of sustained transmission is low.”

This, we now know, was catastrophically untrue, and in the months since, the global pandemic has put much of the world under an unprecedented lockdown and killed more than 100,000 people.

The U.S. was also slow to recognize the seriousness of this new coronavirus, which caught the entire country unprepared. President Donald Trump has blamed the catastrophe on any number of different actors, most recently, singling out the WHO. “They missed the call,” Trump said about the body at a briefing this week. “They could have called it months earlier.”

Trump may well be looking to deflect blame for his own missed calls, but inherent structural problems at the WHO do make the organization vulnerable to misinformation and political influence, especially at a moment when China has invested considerable resources cultivating influence in international organizations whose value the Trump administration has questioned. (Trump just in March announced he would nominate someone to fill the U.S. seat on the WHO’s Executive Board, which has been vacant since 2018.)

Even in January, when Chinese authorities were downplaying the extent of the virus, doctors at the epicenter of the outbreak in Wuhan reportedly observed human-to-human transmission, not least by contracting the disease themselves. In the most famous example, Dr. Li Wenliang was censured for “spreading rumors” after trying to alert other doctors of the new respiratory ailment; he later died of the virus himself at age 33. China now claims him as a martyr. Asked about Li’s case at a press conference, the executive director of the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, Michael Ryan, said, “We all mourn the loss of a fellow physician and colleague” but stopped short of condemning China for accusing him. “There is an understandable confusion that occurs at the beginning of an epidemic,” Ryan added. “So we need to be careful to label misunderstanding versus misinformation; there's a difference. People can misunderstand and they can overreact.”

Those lost early weeks also coincided with the Chinese New Year, for which millions of people travel to visit family and friends. “That’s when millions of Wuhan people were misinformed,” Xiao said. “Then they traveled all over China, all over the world.”

The WHO, meanwhile, was getting its information from the same Chinese authorities who were misinforming their own public, and then offering it to the world with its own imprimatur. On January 20, a Chinese official confirmed publicly for the first time that the virus could indeed spread among humans, and within days locked down Wuhan. But by then it was too late.

It took another week for the WHO to declare the spread of the virus a global health emergency—during which time Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO’s director-general, visited China and praised the country’s leadership for “setting a new standard for outbreak response.” Another month and a half went by before the WHO called COVID-19 a pandemic, at which point the virus had killed more than 4,000 people, and had infected 118,000 people across nearly every continent.

The organization’s detractors are now seizing on these missteps and delays to condemn the WHO (for which the U.S. is the largest donor), call for cutting the organization’s funding, or demand Tedros’s resignation. At the White House, Trump’s trade adviser Peter Navarro has been a sharp critic.

“Even as the WHO under Tedros refused to brand the outbreak as a pandemic for precious weeks and WHO officials repeatedly praised the [Chinese Communist Party] for what we now know was China’s coordinated effort to hide the dangers of the Wuhan virus from the world, the virus spread like wildfire, in no small part because thousands of Chinese citizens continued to travel around the world,” Navarro wrote to me in an email. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently said the administration was “reevaluating our funding with respect to the World Health Organization;” Trump has said an announcement on the matter will come next week. On the Hill, Republican Senators Martha McSally of Arizona and Rick Scott of Florida are both seeking an investigation of the WHO’s performance in the crisis and whether China somehow manipulated the organization. “Anybody who’s clear-eyed about it understands that Communist China has been covering up the realities of the coronavirus from Day 1,” McSally, who has called for Tedros to resign, told me. “We don’t expect the WHO to parrot that kind of propaganda.” Scott told me he wants to know whether the WHO followed their own procedures for handling a pandemic and why the organization hasn’t been forceful in condemning China’s missteps.

Asked for comment, a representative from the WHO pointed to a press conference Tedros gave this week. “Please quarantine politicizing COVID,” Tedros said then. “We will have many body bags in front of us if we don’t behave … The United States and China should come together and fight this dangerous enemy.” Even in early January, when it was still describing the disease as a mysterious new pneumonia, the WHO was publishing regular guidance for countries and health-care workers on how to mitigate its spread. And the organization says it has now shipped millions of pieces of protective gear to 75 countries, sent tests to more than 126, and offered training materials for health-care workers.

In any case, it’s not the WHO’s fault if China obscured the problem early on, says Charles Clift, a senior consulting fellow at Chatham House’s Center for Universal Health who worked at the WHO from 2004 to 2006. “We’d like more transparency, that’s true, but if countries find reasons to not be transparent, it’s difficult to know what we can do about it.” The organization’s major structural weakness is that it relies on information from its member countries—and the WHO team that visited China in February to evaluate the response did so jointly with China’s representatives. The resulting report did not mention delays in information-sharing, but did say that “China’s bold approach to contain the rapid spread of this new respiratory pathogen has changed the course of a rapidly escalating and deadly epidemic.” The mission came back telling reporters they were largely satisfied with the information China was giving them.

If this is something short of complicity in a Chinese cover-up—which is what former National Security Adviser John Bolton has alleged of the WHO—it does point to a big vulnerability: The group’s membership includes transparent democracies and authoritarian states and systems in between, which means the information the WHO puts out is only as good as what it’s getting from the likes of Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin. North Korea, for instance, has reported absolutely no coronavirus cases, and the WHO isn’t really in a position to say otherwise.

The structure also gives WHO leaders like Tedros an incentive not to anger member states, and this is as true of China as it is of countries with significantly less financial clout. During the Ebola epidemic in 2014, Clift said, WHO took months to declare a public-health emergency. “That’s three very small West African countries, and WHO didn’t want to upset them,” Clift said. “WHO didn’t cover itself in glory in that one.” The response this time has been much faster and better, in Clift’s observation. “It doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be examined afterwards to see what they could have done better,” he said. “And one should really investigate the origins of what happened in China.”

The WHO has also shown, however, that it can walk the line between the need for cooperation and information-sharing from member states and the need to hold them accountable for mistakes. During the SARS outbreak in 2003, a WHO spokesman criticized China for its lack of transparency and preparation, which had allowed the virus to spread unchecked. China even later admitted to mistakes in handling the outbreak.

No such critique has been forthcoming this time. One study found that China could have limited its own infections by up to 95 percent had the government acted in that early period when doctors were first raising the alarm and the Chinese Communist Party was still denying the extent of the problem. “The WHO at that time didn’t do their job,” Xiao said. “The opposite: They actually compounded Chinese authorities’ misinformation for a few weeks. That is, to me, unforgivable.”

Some Patients Really Need the Drug That Trump Keeps Pushing When he touts hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment, shortages endanger those of us who already take it. By Maya L. Harris

One morning during my last semester in college, I woke up with a strange rash on my face. When it didn’t go away after exhausting a tube of over-the-counter cortisone, my mother persuaded me to see a doctor. The diagnosis was lupus: a life-changing autoimmune disease in which the body literally attacks itself. The physical effects of the disease are cruel, including excruciating joint pain, organ damage, dramatic hair loss, and debilitating fatigue—most of which I have experienced again and again, often for long stretches, throughout my life. And while lupus can be managed, it has no cure.

For three decades, I kept this private and spoke of my condition only with my family and a handful of close friends. I had no intention of changing that until the coronavirus changed everything.

Millions of Americans find themselves vulnerable to COVID-19 because of underlying health challenges, but this pandemic has unearthed particularly deep fractures along our nation’s racial and gender fault lines. This is especially true of lupus. Roughly 1.5 million Americans live with lupus, and we are overwhelmingly female and disproportionately black or brown. For black women like me, lupus tends to take hold at a younger age with more serious, life-threatening consequences. For us, the coronavirus could very well be a death sentence.

Worse still, the pandemic is amplifying the inequities of the health system in tragic ways. For instance: when the president of the United States decided to hype—as a coronavirus treatment—the primary medication used for controlling lupus, he put an already disadvantaged group of patients in even greater jeopardy.

Not long ago, Donald Trump started talking and tweeting about hydroxychloroquine, which I have taken for most of my adult life, as if it were a miracle drug—a “game changer” for treating COVID-19, the president insists. Immediately, thousands of people began hoarding it, causing shortages that have resulted in lupus patients—and their doctors—struggling to get the supply they need. The more Trump pushed the unproven remedy from the White House podium, the more I wondered: Did he not care that the Food and Drug Administration hadn’t approved the drug for COVID-19? Was he that desperate to contain a crisis of his own making?

Trump has even said that people should consider taking hydroxychloroquine preventively. Talking about the drug during a recent briefing, he asked again and again: “What do you have to lose?” But for a president to casually invite Americans to self-medicate is harmful and potentially deadly. And if the supply shortages continue, those of us whose well-being depends on the drug have plenty to lose.

Even on a good day, lupus extracts a physical and emotional toll. There is always the looming possibility that a flare-up could leave you bedridden and racked with pain, and often the only relief comes from this essential medication. Unnecessary shortages caused by false medical narratives peddled from the nation’s highest office not only create fear and anxiety in those who desperately need hydroxychloroquine, but also engender false hopes in those who hoard the drug but might derive no benefit at all from it.

Experts such as Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, have urged caution, pointing out that hydroxychloroquine is unproven against coronavirus and that there’s “only anecdotal evidence” it can be effective. The experience in other countries has been negative to neutral at best. Yet the U.S. government is stockpiling 29 million doses of the drug anyway—and not out of concern for patients with lupus.

Having spent my career as a civil-rights advocate, I’m acutely aware that the people most affected by the hydroxychloroquine drug shortages live in communities or belong to demographic groups that are among the most vulnerable, even in the absence of a pandemic. Black Americans suffer higher rates of not only lupus but a host of other chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and hypertension, making them more susceptible to the coronavirus. This is compounded by structural inequalities that have denied too many black people access to adequate health insurance, employment, housing, and transportation—all keys to high-quality health care in this country.

In addition, for years, racial bias has infected the way medical care is delivered to black patients, whether children or adults, from diagnosis to treatment. Research has supported the growing recognition that medical professionals have too often dismissed black patients’ reported symptoms, such as pregnancy complications and pain. The coronavirus is raising questions anew about such bias, amid stories about black women who have been turned away from hospitals despite displaying severe COVID-19 symptoms.

Because of these and other factors, medical professionals have been warning—for weeks—that the coronavirus would hit the black community especially hard. And now the experts’ worst fears are coming true.

One day, generations will recall with shame and outrage how the federal government foresaw but failed to prevent this unfolding human tragedy. While President Trump continues to make unfounded claims about hydroxychloroquine, others in positions of responsibility—doctors, hospital administrators, and state and local officials—can take steps to ensure access to vital medications for those who need them. For example, the Ohio and Nevada Boards of Pharmacy have limited how much hydroxychloroquine can be prescribed for certain cases—and banned pharmacists from selling it for preventive use.

Even if people with lupus can get hydroxychloroquine, the broader injustices revealed—and reinforced—by the pandemic will remain. For that reason, authorities need to collect more and better data about how the coronavirus is affecting communities of color. A range of other steps—from vastly expanding our mobile-clinic capacity, to targeted outreach, education, and testing—would also help overcome years of disinvestment and bias in the medical-delivery systems on which people of color depend.

These measures are not aspirational. They will save lives now—which is more than can be said for Trump’s false narratives about a miracle drug.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

What Will Happen if the Coronavirus Vaccine Fails? A vaccine could provide a way to end the pandemic, but with no prospect of natural herd immunity we could well be facing the threat of COVID-19 for a long time to come. by Sarah Pitt

There are over 175 COVID-19 vaccines in development. Almost all government strategies for dealing with the coronavirus pandemic are base...