In a future of multilateral alliances and blocs, Pakistan would be well advised to choose its allies carefully. In the event of becoming a vassal state of China, it will primarily have itself to blame.

Pakistan has made several major grand strategic mistakes since its creation in 1947, including the attack on India in 1971, which led to Pakistan’s dismemberment. However, Pakistan is in the midst of making another grave mistake, and it is one seldom discussed. This is the high cost of its alliance with China. Due to the poverty in its long-term, strategic planning, Islamabad’s conception that the Sino-Pakistani alliance is key to Pakistani security introduces dependence on Beijing and creates the avenue for Beijing’s exploitation and manipulation of it—with the result that Pakistan finds itself less secure and alone in the world. We argue that Pakistan should reverse course. The alliance with China ultimately serves China’s ambitions above Pakistan’s. Islamabad should extricate itself from its alliance with China, and improve its position by aligning with other, democratic states.

The rise of China has had profound impact on Pakistan’s strategic calculations. A more powerful and outwardly amicable China causes a natural reaction in Pakistan to align itself more closely with China in order to balance against India, its long-term adversary. Pakistan’s leadership believe that an alliance with China will somehow replace the long-term Pakistani dependence on the United States in mediating its relations with India. They also think that this relationship will help improve Pakistan’s poor economic situation.

To the contrary, Pakistan’s strategic choice to ally with China is a profound mistake. Before it gets drawn even closer to China, Pakistan should rethink its strategic choices. The alliance with China is a strategic blunder because China is a poor alliance partner. Islamabad should note that China has tended to treat its allies as subordinates instead of partners in shaping its geostrategic ambitions. Indeed, Beijing has not been subservient to any state since the Sino-Soviet split by the late 1950s. China’s steadfast allies are Cambodia, Iran, Myanmar, and North Korea—hardly an august group. Beijing’s relationship with Moscow underscores the authoritarian character of its alliance relationships. China’s behavior as an alliance partner is often boorish, exploitative, and Machiavellian.

China’s economic assistance to Pakistan has come with very high costs. It has vowed to invest up to $60 billion in Pakistan as part of the CPEC but most of this investment will be extended in the form of loans—with a high interest rate of up to 7 percent. Sooner rather than later, Pakistan will find itself unable to service these very costly debts held by China. As it is rapidly moving all its eggs into the Chinese basket, it will quite likely have to enter a “debt-for-equity swap” with China—something that Sri Lanka recently had to do when it was unable to service its Chinese debts. The Sri Lankan deal handed China control of the strategically important port of Hambantota (and fifteen thousand acres of surrounding land) for ninety-nine years. The current Sri Lankan government is trying to extricate itself from such arrangements put in place by the country’s previous administration.

Along with helping Pakistan deal with its imminent economic woes, China has also expressed interest in building a naval base at Jiwani in southwest Pakistan. Jiwani is located around eighty kilometers west of the Gwadar Port (another venture developed by the Chinese). The town is only fifteen miles away from the Iranian border. Perhaps not entirely coincidentally, the Iranian port of Chabahar, developed jointly by Iran, India and Afghanistan, is only a stone’s throw away from Jiwani. The Jiwani base will enable the Chinese navy to service its fleet in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean region, which is present to provide support to the country’s commercial shipping in the region.

Allowing China a military presence in Pakistan is harmful for the country for the following reasons: Pakistan will take a hit to its sovereignty, and the Pakistani military and civilian leadership will have little-to-no say in determining how China decides to use that facility. Also, the Chinese military presence on Pakistani soil will make Pakistan a target in the event of a clash between China and India. The Chinese interest in Pakistan’s northwest has already raised eyebrows in New Delhi, which remains hopeful that its Chabahar port in Iran will allow it to enter the regional market in Afghanistan and Central Asia. India has invested a great deal in that venture and would not like the port to be under any threat. The potential for conflict will grow.

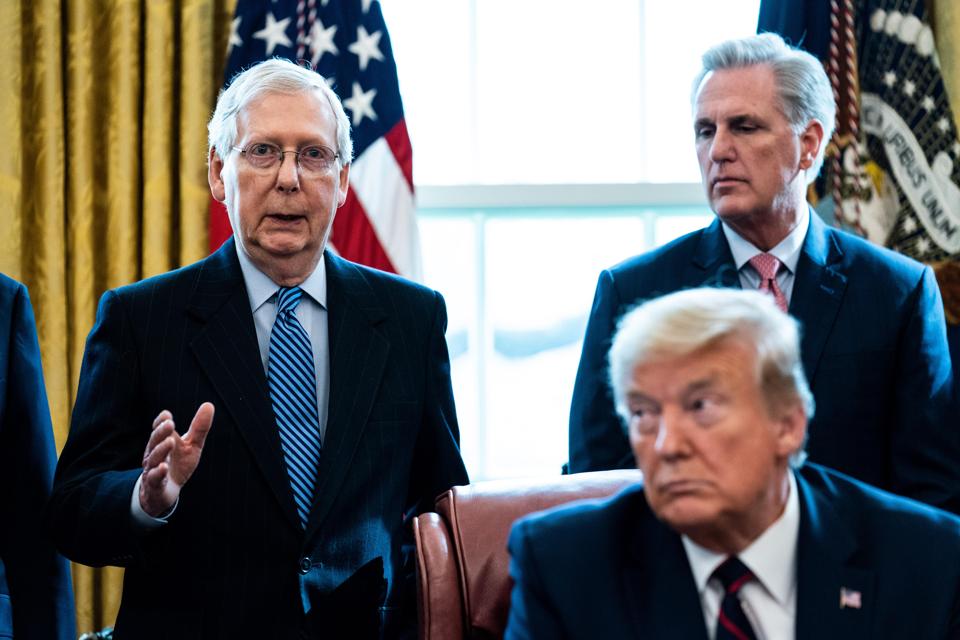

On the other hand, Pakistan’s relations with the United States have continued to spiral downwards, in particular, since the arrival of the Trump administration in office. Washington has long criticized Pakistani sponsorship of terrorist groups in Afghanistan that have made it hard for the United States to extricate itself from the Afghan quagmire. The administration has also decided to cut U.S. aid to the country, which amounted to approximately $1.3 billion per year.

Instead of serving Pakistan itself, the country’s alliance with China paradoxically serves India’s interests. For India, a lonely and isolated Pakistan in tight embrace with China is the best possible option. This relationship makes Pakistan more isolated in the international community. In the event of a clash between India and Pakistan, New Delhi will call upon Washington’s assistance as it has done in the past. Equally, India would be likely to tout Pakistan’s support from an authoritarian China. On the other hand, Pakistan will lose that potential avenue of conflict resolution and path to pressure India. Alignment with China only ensures opposition to Pakistani interests in Washington. That situation is welcomed in both New Delhi and Beijing because China desires some degree of tension between India and Pakistan as this increases its leverage in Islamabad.

A near-term or quick reorientation of its strategy would be unthinkable for Pakistan. Rapid grand strategic changes do happen in international politics, but they are rare. Nonetheless, Pakistan can commence by taking five steps, which will place it on a path to greater security and freedom of action. First, Islamabad can begin to create a little bit more distance between itself and Beijing by not accepting the latter’s every demand but demonstrating independence of action and policy when the People’s Republic of China adversely impacts Pakistan’s interests.

Second, it can also start openly criticizing China’s exploitative economic policies and human-rights violations, such as its treatment of its Muslim Uighur minority in Xinjiang. China has suppressed this minority for many years. However, its repression has gotten much worse. Beijing has initiated a crackdown which includes imprisoning at least 120,000 in “re-education” camps, heightened surveillance, curtailing freedom of movement and Islamic religious practices by limiting marriage ceremonies, children’s names, and facial hair.

Third, it can also negotiate better terms that prevent China from reaping significant benefits from its relationship with Pakistan. At a minimum, the relationship should entail that Pakistan is an equal and not subordinate member, and Islamabad should be open to requiring the renegotiation of existing contracts.

Fourth, Pakistan would be better off to not allow any Chinese military presence on its soil. Any such access would jeopardize Pakistan’s security in the future.

Fifth, Pakistan should endeavor to win over the Trump administration, which has shown itself amenable to opening avenues for dialogue. Islamabad would do well to realize that the Trump administration’s worldview reflects a post–Cold War mindset and the United States is looking to make up for the strategic neglect of the last two presidents.

There does not exist much rationale for Pakistan to justify its embrace of authoritarian states. It remains to be seen whether authoritarian states like Turkey, Russia and China are able to influence the contours of the international system in the future. There are strong arguments against this, including the fragility of the political systems in China and Russia, endemic economic problems and corruption, adverse demography, and environmental disasters. Pakistan would be well advised to avoid them.

In a future of multilateral alliances and blocs, Pakistan would be well advised to choose its allies carefully. In the event of becoming a vassal state of China, it will primarily have itself to blame. A closer relationship with Western democracies will build on the close societal links Pakistan enjoys with states in Europe and North America. It is not certain whether the dragon will easily let Pakistan extricate itself from its embrace, but Pakistan has every motivation to escape its grasp before it becomes impossible to do so.