Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) has always wanted Congress to take a more active role in foreign policy. Now, it’s more urgent than ever.

Murphy is quickly stepping into his role as the “McCain of the left” —the face of foreign policy consensus in the Democratic Party.

Over the past five years, he spearheaded the opposition against U.S. involvement in Yemen, helping push Congress to pass its first war powers resolution in history. And he’s met with political players around the world, from Ukrainian protesters to the foreign minister of Iran.

The United States is stumbling into an era of great power competition with one hand tied behind its back, Murphy now warns, and the next administration and the current Congress both have to play a role in fixing the damage.

The National Interest spoke to the senator about issues around the world, from the coronavirus pandemic to the political crisis in Venezuela. Below is a transcript of the conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

Great to meet you, Senator Murphy. Thank you for your time. I know it’s pretty busy for everyone, especially with coronavirus. That’s why I wanted to talk to you.

You’ve long been an advocate of Congress taking a bigger role in foreign policy, which is gaining more and more traction, especially on the progressive side of things. Could you tell me how Congress could play a more productive role in this global crisis that’s calling into question U.S. leadership?

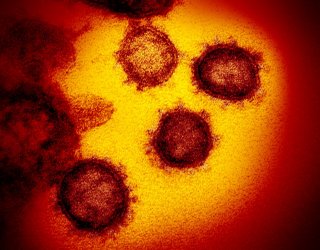

The virus is a clear indicator that a threat can emerge to the United States on the other side of the world, and result in the death of tens of thousands of Americans within months. When it comes to non-conventional threats like pandemic disease, borders don’t matter. Today, with the Trump administration, you’re witnessing the consequences of our withdrawal from the world.

We took two thirds of our scientists out of China in the years approaching the breakout of coronavirus. We shattered our alliance with our European partners just at the moment that we needed to be working with them to hold China to account, make sure that we have enough medical equipment in the United States to fight the disease.

We are walking away from the WHO [World Health Organization] at the moment when only WHO can effectively stand up a future global public health infrastructure that can stop the next pandemic.

We warned the administration that there would be consequences for its wholesale retreat from the world, and we are now living with those consequences.

You ask what Congress can do. Congress has largely abdicated its responsibility to be a coequal branch with respect to foreign policy. Now is the time for Congress to step up.

We could pass legislation requiring the administration to rejoin the WHO. We could pass legislation joining the United States to the global vaccine development effort.

We could pass legislation increasing foreign aid to make sure that we’re beating the virus everywhere, because we know that so long as it exists in a refugee camp somewhere in the Middle East, it’s still a threat to the United States

Congress has lots of mechanisms by which we could stand up the kinds of public health programming that are needed to muster the short-term and long-term responses we need to pandemic disease.

You’ve said that “the reason we’re in this crisis is not because of anything China did,” because we should have been prepared for it ourselves, but a lot of Republicans have introduced this idea that China should somehow be held to account or “pay” for the pandemic.

Where do you stand on this issue, and are there areas where you do think we need to push back harder against the Chinese government?

Well, first, I advise you to watch the whole clip, not just the three words that were picked out of it, because what I’ve said has been consistent: China bears responsibility for its efforts to cover up the initial extent of the virus and its continued efforts to obfuscate the scientific information we need to develop vaccines and treatments.

But there was no greater cheerleader for China’s coverup in January and February than President Donald Trump. On twelve different occasions, he praised China’s response. He lauded their transparency.

He was asked a point-blank question on February 7th as to whether China was covering up anything about the virus. He said, “no, they’re running a model response.”

Nobody frustrated the world’s efforts to try to get China to change its early behaviors more than Donald Trump did.

My point is that, while China bears much responsibility for this crisis, it was not inevitable that a hundred, two hundred thousand Americans had to die. The president has run an abysmal response to the virus, which has resulted in it being much worse in the United States than it had to be.

And so there’s lots of responsibility to go around. The Chinese bear much of it, but there is no way that the mistakes made in China needed to result in seventy thousand, a hundred thousand, or two hundred thousand Americans dying.

The question is, what do you do about it? Is the right response to withdraw from the WHO? Because if your complaint is that China has too much influence at the WHO, you essentially are exacerbating the problem that you’re seeking to solve by pulling the United States out.

I just haven’t seen any action from this administration that actually addresses the complaints they make about China.

Another country that’s been struck with the coronavirus, and has maybe been criticized for its own lack of transparency, is Iran. You and several other members of Congress have called for engagement with Iran over this coronavirus crisis, which the Trump administration has really been dragging its feet on.

How do you think the United States should be engaging Iran, both on coronavirus and in general, and what role should Congress be playing in this?

The case that we tried to make is that the Iranian people are not our adversary. The Iranian regime is our adversary. That’s a hard case to make when our sanctions are, in part, responsible for the death of innocent civilians due to coronavirus.

There’s no doubt that our current sanctions make it harder for Iran to stand up a response to this epidemic.

And our sanctions make it easier for the Iranian regime to make the case to their people that it’s the United States that’s standing in the way of medicines and medical technologies being delivered to the Iranian people.

The regime’s always engaged in propaganda that’s divorced from the truth, but it is true that our sanctions are hindering the Iranian medical response. What I think we should be doing is making sure that none of our sanctions are resulting in innocent people in Iran dying of coronavirus. I also think this is an opportunity for engagement.

This is a moment when the number one threat to Iran and the number one threat to the United States is the same thing—a virus. It could be a mechanism by which we could start talking to each other.

The Trump administration has said from the beginning, whether you believe them or not, that their goal is engagement, and that they see sanctions as a pathway to engagement. Maybe this isn’t the pathway that you initially envisioned, but it’s an opportunity, and right now, it’s an opportunity that the administration is ignoring.

I’m wondering specifically what you think Congress’ role in this can be, because a lot of these sanctions are up to executive discretion, but Congress also holds a lot of power over this.

There’s a majority in Congress that voted for the war powers resolution. I’m wondering what opportunities you see there.

Very few.

I think, A, it’s difficult for Congress to micromanage sanctions policy. What I’m talking about is nuanced: decisions about what is subject to and what is exempt from sanctions.

B, there’s just not the political will in the Senate with Mitch McConnell as majority leader to pass a bill that eases medical-related sanctions on Iran today.

I just think, realistically, this is an endeavor the administration has to undertake.

I know that you met with Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif in Munich. He had said, after meeting with a different senator, that he engages with American lawmakers “just for clarifications, not for negotiations.”

I’m curious how he approached his conversation with you.

I’ve met with Foreign Minister Zarif on a number of occasions. I’ve met with him during the Obama administration and during the Trump administration.

That is my responsibility as a member of the [Senate] Foreign Relations Committee, to meet with foreign ministers, frankly regardless of whether they’re coming from a friendly country or an adversary.

My belief is that it’s important to keep dialogue open with Iran, even if that’s just through informal parliamentary channels. When I’m talking to Zarif, I’m not negotiating for the United States of America, just like when I’m talking to the French foreign minister, I’m not negotiating for America.

The administration conducts official international negotiations, not the Congress, unless the Congress is specifically authorized to do so.

There’s a big looming deadline with the arms embargo on Iran about to expire. You told Al-Monitor two months ago that you’d support trying to re-up this embargo and “the nuclear deal doesn’t exist today,” so we would need more leverage going back into it.

Right now, the Trump administration is hinting that they want to re-up the arms embargo with this controversial unilateral snapback mechanism. Russia has said that it’s a non-starter, Iran has said that this will cause the deal to “die forever,” and the Europeans don’t seem very thrilled with it.

Do you think this is the path to go down to restore the embargo, and if so, how much political capital should we be willing to spend on it?

The JCPOA [nuclear deal] does not exist any longer. We violated the terms of the agreement, and thus compliance with it by other parties is now voluntary. It’s ridiculous for the administration to suggest that it can pick and choose the parts of the JCPOA that it wants to observe and enforce.

That’s a wonderful way to approach an international agreement: “I will not comply with the portions that my country is subject to, but I expect you to the portions that your country is subject to.”

I believe that the arms embargo is important and it needs to stay in place, and I think the Trump administration has put us in an awful position, because it is harder than ever to reimpose the arms embargo outside of the JCPOA.

I don’t have a lot of creative advice for the administration, other than get back inside the JCPOA, because if you’re inside the JCPOA, it makes an arms embargo much easier to reinstate.

They just vetoed the war powers resolution [related to Iran], which, if I’m correct, is the second time both houses of Congress have ever passed one. The first one was the Yemen war, which you were very much a part of. I’m curious why you chose Yemen as the test case for taking back war powers for Congress from the executive.

Obviously, Yemen and Iran are very different. We were and, to an extent, still are, actively engaged in fighting in Yemen. There’s a partial ceasefire today, but during most of the last five years, the United States has been actively involved in a war inside Yemen without authorization from Congress.

The Iranian war powers resolution is a little different, because we are not actively engaged in active hostilities with Iran. That war powers resolution was, frankly, more forward-looking to make sure that we didn’t fall into an unauthorized war with Iran.

But in Yemen, there were people dying every day due to U.S. planes and U.S. bombs.

It was a war that was making the United States less safe, every single day. Al Qaeda and ISIS were growing their power every day inside Yemen. Yemenis were being radicalized against the United States. The humanitarian catastrophe was being looked upon globally as the responsibility of the United States. It was cratering our reputation internationally.

It was a disaster on all fronts. I felt it was imperative that we pull the United States out of it. I still feel that way.

I’m glad that Congress passed the war powers resolution, and I’m sorry that the president still sees fit to blindly follow the Saudis into a war that may be in the Saudis’ best interest but is certainly not in ours.

We’re going to jump all the way across the world [now]. In Venezuela last week, we saw this very bizarre armed clash—it’s unclear exactly what happened, but apparently there were Americans involved.

You told the Trump administration that “[e]ither the U.S. government was unaware of these planned operations, or was aware and allowed them to proceed. Both possibilities are problematic.”

What do you think we could be doing better in terms of our Venezuela policy, both in terms of the incident that just happened and our more general stance towards [rival claimants to the Venezuelan presidency] Guaidó and Maduro?

Our Venezuela policy has been an absolute disaster. All it’s done has made Maduro stronger. It’s built on fantasy, and it needs to be based on reality.

What we did was play all of our cards right at the initial moment, which is generally Trump’s overall strategy in foreign policy. There’s no nuance. There’s no strategy. There’s no long-term play.

We should have built a regional and international coalition to ratchet up pressure on Maduro, and give him a way out. Instead, we immediately recognized Guaidó.

We put perhaps the worst possible person in place as our envoy—a capable diplomat, but somebody who is ready-made to be cast as an American imperialist by the Venezuelan regime.

And ultimately, we came off looking powerless, weak, and feckless, because we backed Guaidó and we couldn’t do anything about it.

I think it’s really hard to restart at this point. I’ve suggested imposing an aid-for-food program, in which we—I’m sorry, an oil-for-aid program—in which we relax some of our sanctions policy in exchange for any revenues going directly to aid the Venezuelan people.

I think that our totally dysfunctional relationship with Russia and China greatly hamstrings our ability to try to pressure the Venezuelan regime. The next administration’s going to have to find a way to work with Russia and China on Venezuela policy.

Having no diplomatic relationship with Cuba also hurts.

The Trump administration is in a position where they can’t win in Venezuela, and the next administration is going to essentially have to restart our Venezuela policy from scratch.

I don’t know what happened last week. I trust that the American government wasn’t involved. But if we didn’t know that this operation was being planned, that shows you how disconnected from reality we are inside the country.

We’re going to get another administration in either less than a year, or in four years. What’s your advice to them to undo the damage that’s been incurred?

The first thing Joe Biden’s going to have to do is convince hundreds of capable diplomats who fled the Trump administration to come back. We simply don’t have the personnel right now to represent the United States abroad. We’re going to have to restock our diplomatic corps.

Second, a Democratic administration is going to have to recognize that we are [unintelligible] in terms of where our resources are. We’re spending $13 billion on global public health today compared to $740 billion on military operations. That makes no sense.

We’re going to have to change the way that we spend our money.

And we’re going to have to do some hard work to prove to the world that the Trump administration’s wholesale withdrawal from global institutions was an anomaly.

There’s just not as much room as there used to be at the table for the United States, because China has taken up so much of it.

We’re going to have to do some hard work to rejoin international forums and convince countries to join us, rather than the Chinese, who have gradually stepped into the vacuum we’ve created.