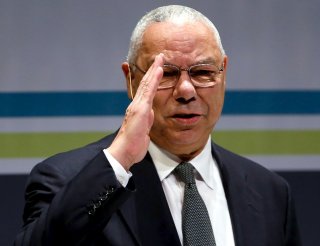

Interviewed by CNN host Jake Tapper over the weekend, retired Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell was asked whether he agreed with the denunciations of President Trump issued by James Mattis and John Allen, both retired Marine four-star generals and, in Mattis’ case, Trump’s first defense secretary.

“You have to agree,” replied Powell. “I’m watching them closely, because they all were junior officers when I left, and I’m proud of what they’re doing. I’m proud that they were willing to take the risk of speaking honesty and speaking truth to those who are not speaking the truth.” Herein lies the rub: The current crisis in civil-military relations — and, regardless of how one regards Trump, the parade of partisanship on the part of the most senior, experienced, bravest, and otherwise wisest military men of the last 30 years ought to be disturbing — can truly be said to be Powell’s in the making. The model of a modern political general was cast in Powell’s image and has shaped the behavior of Mattis, Allen and their like, including Michael “Lock-Her-Up!” Flynn. This “Powell Generation” has behaved with increasing disregard for the norms of apolitical professionalism that have long constituted the ethos of the American officer corps.

Powell reminded Tapper that he’d “been out of the military for 25 years now,” so it might seem a stretch to lay such a heavy charge on Powell. But two of the signature moments of his tenure as JCS chairman are worth recalling, and can be understood at greater length by re-reading the prescient critique by Richard Kohn, the leading historian of American civil-military relations, published in The National Interest in 1994. The first telling tale is to be found Powell’s iron-fisted and manipulative grip on the planning for Operation “Desert Storm,” the Iraq war of 1991. Indeed, by Powell’s own admission, he positioned himself as the “arbiter of American military intervention overseas,” a role the Constitution reserves to civilians. Quoth Powell:

[Our] military advice was shaping political judgments from the very beginning. … We were able to constantly bring the political decisions back to what we could do militarily. And if there’s one story that is going to be written out of Desert Storm and [the invasion of Panama,] Just Cause and everything else we’ve done, it’s how political objectives must be carefully matched to military objectives and military means and what is achievable.

Powell had for a year taken very public stances in support of the existing policy on excluding homosexuals, in spite of the comparison with earlier discrimination against African-Americans and the heat he must have taken from civil rights advocates and allies in the African-American community. General Powell must have felt very strongly indeed on this subject, for he virtually defied the President-elect, never denying publicly the rumors in November-December 1992 that he might resign over the issue, doing nothing to scotch rumors that his fellow chiefs might do the same, doing nothing to discourage retired generals from lobbying on Capitol Hill to form an alliance against lifting the ban. General Powell and the Joint Chiefs then appeared to negotiate publicly with the President at a meeting in late January 1993 – and privately through the Secretary of Defense, the press, and Congress – for the compromise finally forced on Bill Clinton last summer. On this issue, the military leadership took full advantage of a young, incoming president with extraordinarily weak authority in military affairs. Nothing did more to harm the launching of the Clinton administration than “gays in the military,” for it announced to Washington and the world that the President could be rolled.