Since mid-March, the World Health Organization has urged countries to scale up the testing, isolation and contact tracing of COVID-19 patients in order to combat the pandemic. The reason for this advice is that if you can find infected cases, isolate and treat them, and trace the close contacts who they might have infected, and isolate them too, then you can keep much of the infection out of the general population.

This stops its spread and slows down the speed of the epidemic. It seems a simple and obvious strategy. It has been used extensively in the past, for example to stop epidemics of smallpox and Ebola. So why hasn’t every country done that? Well, it’s not as simple as it appears.

The efficiency of contact tracing in any epidemic depends on the characteristics of the infection and the speed and coverage of the tracing process. So when a new disease such as COVID-19 first emerges it’s not possible to know exactly how useful testing and tracing will be.

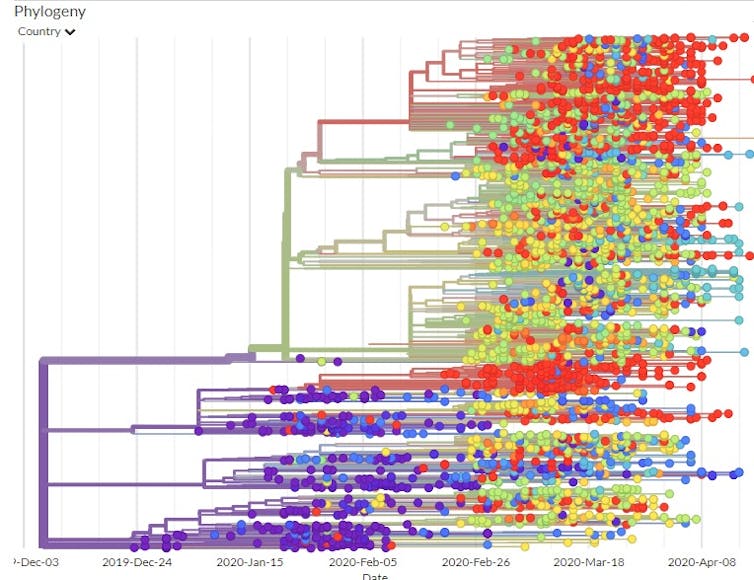

Testing and tracing is most feasible as an effective strategy at the start of an outbreak when there are just a few chains of transmission of the disease. But if this does not keep the epidemic under control, and there is widespread community transmission, there will quickly be many cases and contacts. This is especially the case with a disease such as COVID-19, which is easy to catch, is quickly passed on after an infection sets in, and can infect some people without producing symptoms.

Many people will be getting infected from unknown cases and a large proportion of the population would need to be isolated. Testing and tracing soon becomes an unmanageable strategy and a lockdown to reduce physical contact then becomes a more efficient and effective means of controlling the epidemic. This achieves the same thing as testing and tracing, by keeping much of the infection out of the general population, but is a blunter instrument as it targets everybody.

As the current pandemic developed, some countries, including South Korea, were able to use testing and tracing to control the disease and avoid mandatory lockdown measures. But more widely, identifying cases of the disease with testing did not keep pace with the geographical spread of infection around the world. So in other countries, such as the UK, case finding and contact tracing capacity became overwhelmed early on and lockdowns were introduced instead.

In hindsight, those countries which persisted with expanded and rigorous testing and tracing programmes, such as Germany, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and New Zealand, have fared better with lower deaths rates than those which did not, such as Belgium, France, Italy, Spain, UK and the USA. This is probably because contact tracing and testing can identify asymptomatic infections and isolate them faster than systems relying on the development of symptoms.

Lockdowns aren’t sustainable in the long term because of the social, economic, and physical and mental health effects. The should reduce the spread of the disease so the number of cases starts falling. But if restrictions are relaxed even cautiously then transmission will go up again.

However, with a testing, tracking and tracing strategy in place as well, it will still be possible to keep the epidemic under control. To make this feasible, the numbers of cases needs to come down to a more manageable number, say a few hundred active cases. This is because of the sheer numbers of cases and contacts involved, each of whom would need quarantining until shown to be uninfected. As examples, the average number of tests required per case was 52 in South Korea, and 64 in Australia.

Building testing and tracing capacity is not easy. To start with there are two main types of test you can perform, one that tells you if someone is currently infected (a PCR test) and another that tells you if someone has had the disease in the past (an antibody test). You need the organisational capacity, the labs, equipment and chemical reagents to be able to conduct these on a massive scale.

Contact tracing also requires significant resources. You need thousands of people to interview patients, identify everyone they may have come into contact with since being infected, and track down these contacts. Many countries are also using or planning to introduce contact tracing apps that track your location or identify contacts using Bluetooth in order to automatically gather this data and inform people if they need to self-isolate.

Digital tracing

It is generally agreed in public health circles that these apps are useful as a supplement, but cannot replace manual checking. However, some evidence suggests that COVID-19 spreads too quickly for manual tracing alone, and that an app could help stop the pandemic if 60% of the population downloads it. On the other hand, there are also privacy concerns over how these apps allow governments to track citizens’ movements.

In South Korea the testing was conducted on a base of well-funded and efficient public services and an effective infrastructure, including widespread digital surveillance. For other countries to emulate this success, much still needs to be done in terms of planning, organisation and logistics.

In the UK there are plans to recruit and train 18,000 tracing staff to reintroduce contact tracing. The government aims to conduct 100,000 tests per day, which is about 0.15% of the population.

For the future, it is likely that some form of physical distancing will be required to prevent future waves of infection until an effective vaccine is widely available. These measures, which may need to be periodically tightened and relaxed, should be supported by testing and tracing to keep the number of new infections under control. This is likely to include the testing and quarantining of all new arrivals in a country, to prevent the infection being reintroduced from abroad.