The memes came first.

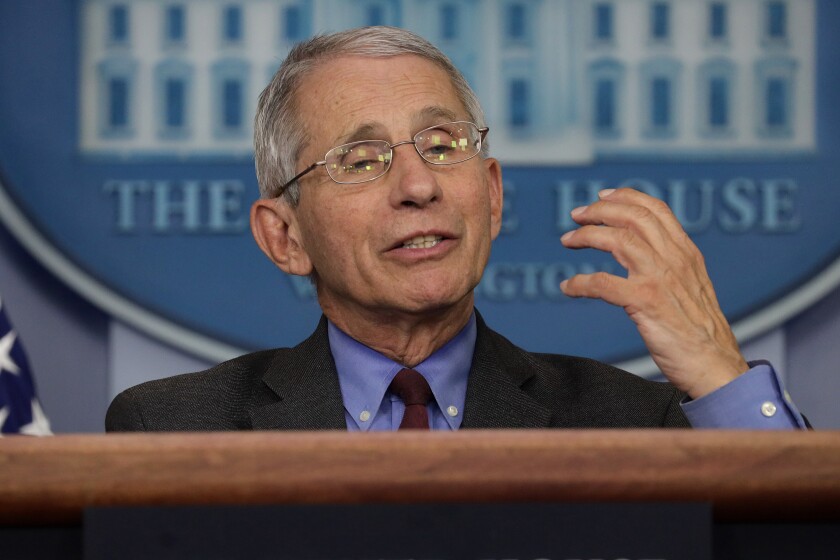

A two-second grimace and a face-palm were all it took to launch Anthony Fauci into the internet’s collective conscience—his reaction to President Donald Trump’s criticism of the “Deep State Department” during a coronavirus task-force briefing in mid-March.

Immediately, the hashtag #FauciFacepalm started trending on Twitter; scores of TikTok videos (including one set to One Direction’s “What Makes You Beautiful”) flooded the platform; and, as my colleague Kaitlyn Tiffany has reported, lustful confessions of Fauci’s sex appeal popped up everywhere.

Then came the guest appearances by the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: a podcast interview with the sharp-tongued hosts from Barstool Sports, a chat with the NBA star Steph Curry on Instagram Live, a live-stream with Mark Zuckerberg on Facebook, and appearances on four popular YouTube channels.

Fauci has developed the kind of internet presence that many public figures, politicians especially, only dream of building. It’s partially the product of his gameness to go on unconventional digital platforms, but it’s organic too. The denizens of the internet have chosen to make him ubiquitous, a privilege reserved for those who demonstrate authenticity, relatability, and trustworthiness. In Fauci’s case, the 79-year-old immunologist has used this influence to inform Americans about the coronavirus and debunk myths, even as his status within the administration has become more precarious over time.

“There’s a weird thing where the internet, the meme culture, has to kind of approve and bring people in … You can’t force yourself into the culture. Fauci didn’t try,” said 19-year-old Kai Watson, who recently analyzed Fauci’s omnipresence in a YouTube video. “That’s why people love him.”

Using social-media platforms, influencers, and memes to spread issue awareness or political messages isn’t new. The 2020 election has already been branded “the year of the influencer,” after Democratic presidential hopefuls tried (and mostly failed) to leverage support from online stars to boost their popularity among young voters. Podcasts such as The Joe Rogan Experience, The Ben Shapiro Show, and Pod Save America are must-stops for some political figures.

What’s different about Fauci is his willingness to speak to young and diverse communities on the platforms they use most—and his ability to do it really well, says Mike Varshavski, a family-medicine physician and YouTuber who has partnered with Fauci.

“There’s no filter there,” Varshavski, who goes by Doctor Mike online, told me. “You end up realizing that this is a human sitting in front of you, not a political candidate. And the more we can humanize politicians, health-care experts, the more people are going to believe them and trust them—because they know how they think.”

Fauci’s approach stands in sharp contrast to, say, Michael Bloomberg’s: To get the former New York mayor’s name and message across, his presidential campaign tried to pay influencers to post about him. The effort fizzled shortly after it began. The strategy came across as cold, calculated, and disconnected from how young people use social media, Watson told me.

Watson and his high-school best friend, Chase Steele, both from Redmond, Washington, run a small YouTube channel where they recently discussed Fauci’s internet presence after seeing him pop up on the site’s homepage as a featured guest on the four popular shows. In each tight, 15-minute segment, Fauci fielded a range of questions about the coronavirus and COVID-19’s infectivity, the government’s response, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s social-distancing recommendations. (Fauci’s office did not respond to requests for comment on this story.)

The YouTube channels Fauci joined (hosted by Varshavski; the comedian Lilly Singh; the news commentator Philip DeFranco; and Trevor Noah, whose Daily Show maintains a lively presence on the platform) have a combined audience of 33 million people. Many of them are young, diverse Americans who don’t usually tune in to cable or network news, but who need to be informed about the virus. Each Fauci video has racked up more than 4 million views; Varshavski’s has garnered more than 5.3 million since March 29.

“The fact that he can come on a show like mine, like Trevor Noah’s, like Philip DeFranco’s—he’s reaching millions of people that it’s gonna have a direct impact on,” the 30-year-old Varshavski told me. “They otherwise would have been unknowingly possibly spreading this virus, spreading misinformation, and it really just pulls them into our corner as advocates.” YouTube approached the White House task force after Fauci’s interview with Barstool Sports, a task-force official told me.

Since the beginning of the outbreak, public-health experts have been especially concerned with the increased risk of community spread of COVID-19 among younger Americans, who might contract the virus, not present symptoms, and go about their lives infecting others. Reports of Mardi Gras revelers and Florida spring-breakers fueled these concerns—and intergenerational strife. (After some older Americans placed the blame on Millennials, the latter group quickly clarified that most of the pandemic partiers were members of Gen Z.)

When their friends began to return from college and local high schools moved to holding classes remotely, Watson and Steele worried that young people would not take social-distancing guidelines seriously. Watson, who was traveling home from a trip to Europe around the time Italy announced its national lockdown, told me he saw his friends posting Snapchats about upcoming spring-break trips to Mexico, and others joking about how they would have to party at home if they couldn’t go abroad.

The Fauci face-palm changed things. Although Watson and Steele had heard the doctor’s name plenty of times on cable news since the outbreak began, they didn’t expect their friends to know him well. But Watson said he soon began to see friends repost and share Fauci memes that doubled as social-distancing recommendations. They noticed more of their friends staying home, especially if they had traveled recently. And they were surprised to see an uptick in engagement from younger viewers on their own YouTube discussion of Fauci’s interviews.

Many young Americans trust Fauci because of the memes, Steele suggested. They make him seem relatable, humorous, and human, in contrast to the other coronavirus task-force members, who seem more rigid. Memes are “our way of legitimizing somebody,” Varshavski said. “This happens sometimes in a bad way, obviously, but this is a prime example of it happening for a good reason.”

To younger audiences, Fauci’s persona feels familiar. He’s essentially the “Bill Nye of coronavirus,” Watson told me, referring to the well-known science educator and TV personality. And his no-nonsense personality evokes memories of an authoritative but compassionate college professor or high-school teacher, Watson said.

At the same time, Fauci’s online exposure has opened him up to the darker side of internet fame: He’s now the target of scorn from some of the president’s online supporters, and the right-wing memeosphere has developed multiple conspiracy theories about him, including one where Fauci is a Hillary Clinton plant working to undermine Trump.

But the attention and trust that Fauci has accumulated among his internet fans may bear lessons for politicians and government officials who hope to reach younger audiences. Politicians often fail to connect with these online communities, because they wait until the home stretch of a campaign season to ramp up their social-media strategy, or try to pay for an influencer army like Bloomberg did, or deploy celebrity endorsements in ways that don’t resonate with young people.

Fauci’s approach demonstrates respect for the users of social-media platforms, Brent J. Cohen, the executive director of Generation Progress, a youth-engagement group, told me.

“Engaging with young people authentically and consistently and on the platforms that young people prefer is just the best way to build the type of relationships that build the trust that then allow people to look at you as a credible source of information,” Cohen said. “That’s what Dr. Fauci is doing right now.”

Watson and Steele told me they hope other government experts catch on to this strategy. When the 2020 campaign kicks back up, they said, more politicians should go on the podcasts young people listen to, go live on their own Instagram accounts, and “seem like actual people.”

“They don’t have to wear the politics hat all the time,” Steele said.

No comments:

Post a Comment