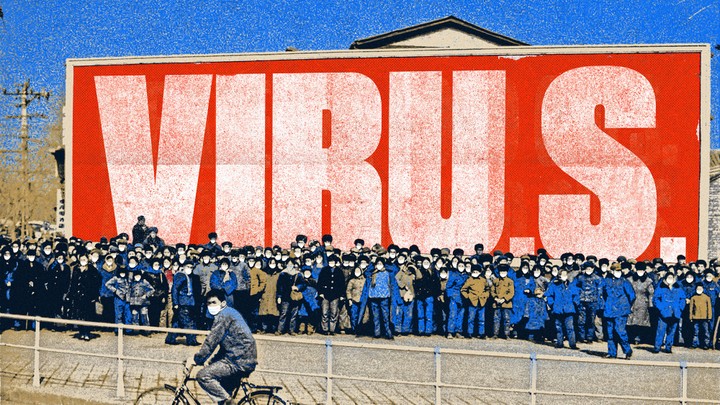

The coronavirus that became a global pandemic first surfaced late last year in Wuhan, China. But according to one common narrative making its way around Chinese messaging apps, an American soldier was patient zero. “Chinese netizens and experts” are urging the United States to release health information about a U.S. delegate who attended the Military World Games in Wuhan, asserted a February 22 story from Global Times. The publication, an offshoot of the Chinese Communist Party organ People’s Daily, insinuated that a U.S. military cyclist might have brought the disease from Fort Detrick in Maryland. Chatter about American origins of the disease had begun a month earlier, in the wilds of China’s chat services and on tiny YouTube channels. That alone wouldn’t have amounted to much; conspiracies are as common on social media as ants at a picnic, and the small accounts speculating about “bioweapons” and “the USA virus” got little early traction.

But this time, Chinese state media picked up the story from internet chatter and turned it into an international phenomenon involving not only official media channels but influential diplomats as well. State channels with massive Facebook followings backed away from prior acknowledgments that the virus had originated in Wuhan, recasting the idea as merely a theory—just one of many unknowns. Zhao Lijian, the spokesman and deputy director general of the Information Department of China’s Foreign Ministry, speculated to his half-million followers on Twitter that the United States was secretly concealing early 2020 COVID-19 deaths in annual flu counts. In an unusually overt act of tinfoil-hat diplomacy, he shared an article from the notorious anti-American crackpot site GlobalResearch. The headline reads, “COVID-19: Further Evidence that the Virus Originated in the U.S.”

While spreading conspiracy theories—stories involving claims that shadowy, powerful interests have secretly engineered events to their own advantage—is a time-honored ploy by which states try to discredit their rivals, the first global pandemic of the social-media era shows just how efficiently wild theories can travel. And as Zhao’s Twitter account shows, state-sponsored propaganda has become deeply entangled with anonymous conspiracy mongering. Authority figures are now legitimizing tropes from the recesses of the internet—and ensuring mass popular awareness of those ideas.

State-sponsored media have long played a role in geopolitical power games. Since World War II, the TV, radio, and print media channels of many governments have created what some experts call “white propaganda”: messaging for which official sources claim authorship. (In gray and black propaganda, the origins are partially or entirely concealed.) In the present day, white propaganda has expanded to include the social-network presences of official channels, as well as the individual accounts of bureaucrats and top politicians. Sometimes, the messages these outlets carry are meant for a regime’s own citizens; other times, the outside world.

Messaging from state media also goes by another, friendlier name: public diplomacy. While academics debate the line between propaganda and public diplomacy, in an interconnected world, having the ability to shape narratives is an imperative. The long-term goal is to make people think favorably of the country and its rulers. In other words, it’s a branding exercise. But in the shorter term, state media channels are also used for more direct advocacy campaigns, convincingly conveying an official point of view on specific issues to those outside its borders. In more heated times, this may extend to smearing an adversary’s government, institutions, or policies. But the narrative manipulation around COVID-19 on China’s official state channels has escalated far beyond spin to outright conspiracy.

From the beginning, the Chinese Communist Party has been struggling to manage both domestic and outside perception of its handling of the outbreak of the disease now known as COVID-19. The coronavirus’s rapid spread within China, and its high death toll, triggered a domestic crisis of confidence in President Xi Jinping’s leadership. Although dissent is often quickly censored, Chinese social-media forums were flooded with comments about Xi being “gutless” for not going to Wuhan, among other criticisms. The situation didn’t play any better internationally: The revelation that the Chinese government knew of the outbreak for two full weeks before taking steps to contain it outraged people worldwide and prompted accusations of a cover-up.

As the crisis has begun to recede within China, with Wuhan exiting lockdown and new infections dropping to a trickle, the Communist Party’s public-diplomacy efforts have gone into overdrive: At the Stanford Internet Observatory, where I work, we gathered months of China’s English-language state-media Facebook posts, identifying key themes that were pushed repeatedly: stories of survival rather than deaths, glowing coverage of the “construction miracle” of new hospitals (whose sudden appearance was framed as the result of patriotic engineering ingenuity, rather than as proof of the need to bolster an overwhelmed medical system), and claims that China had bought the world time through its aggressive containment procedures. One remarkable China Daily article from February 20 boasted, “Were it not for the unique institutional advantages of the Chinese system, the world might be battling a devastating pandemic.” The item also slammed international criticism as the result of “ingrained bias against the country.” Other stories presented a rosy revisionist history. State media coverage of the death of the whistleblower optometrist, Li Wenliang, mourned him as a hero, and entirely neglected to mention his detention by police after he discussed the emerging virus in a chat group of close friends. As the writer Louisa Lim put it in Foreign Policy, “China is trying to rewrite the present.”

The Chinese Communist Party has prioritized “persuasion and information management” for years. It has amassed an extensive white-propaganda apparatus since 2000, building and buying TV, radio, and print media, optimizing localized content and messaging in a wide range of languages. Since 2015, it has invested in building a massive English-language presence for its media properties on the very same social networks it has banned within its own border. The English-language Facebook pages for the state-owned newspaper China Daily and the official Xinhua News Agency have more than 75 million followers each; and the China Global Television Network has a following of 99 million; by contrast, CNN has 32 million and Fox News has 18 million. Part of this growth has come from running paid ads on social-media platforms that China’s own citizens are blocked from using. My team has studied hundreds of state-media ads from Facebook’s recently launched political-ads archive. They are targeted at English speakers worldwide. Throughout 2019, the ads frequently involved friendly images of pandas and kittens, highlighted Chinese art and culture, and amplified feel-good political stories.

In February 2020, they took a different turn. The ads began boosting state media coverage of the coronavirus, with dozens of ads praising Xi for his leadership and emphasizing China’s ability to contain the disease. They incorporated hashtags such as #UnityIsStrength and #CombatCoronavirus, predictions of a quick economic recovery, and stories in which world leaders in Italy, Serbia, and elsewhere express gratitude to China. By March 2020, angry ads appeared in the mix, promoting outraged coverage of President Donald Trump’s use of the term Chinese virus.

Of course, Facebook pages for broadcast media aren’t the Communist Party’s only messaging tool. For years, it has also run peer-to-peer persuasion strategies involving influencers, trolls, bots, and commenter armies. The comment legions—called Wumao, or the 50 Cent Army—have been a shadowy presence on China’s internet and message-board ecosystem for more than a decade. The party has also tried using Twitter bots and Facebook sock puppets, including those uncovered during the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Politico and other investigative journalism teams have reported that similar shenanigans are happening in the coronavirus conversation as well, though attribution remains a challenge; connecting hypernationalist activity back to direct orders from the party is difficult.

That managing the narrative is a top priority for the Communist Party is abundantly clear. Among the nine members of China’s task force for managing the COVID-19 response are the party’s policy czar for ideology and propaganda and the director of its Central Propaganda Department.

Political conspiracy theories appear even in the analog propaganda of decades past. Mark Fenster, the author of Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture, describes them as a “populist theory of power” serving an important communication function: helping unite the audience (“the people”) against an imagined secretive, powerful elite. So when state media in China, for example, create or spread these theories, the elite puppet master is the United States, a geopolitical rival. By exposing the villainy of its adversary, the Chinese Communist Party presents itself as a defender of its people.

The “bioweapon” trope is particularly useful, because it can be readily applied to any disease outbreak. During the Cold War, the KGB’s information-operations department was a notorious practitioner of conspiracy as statecraft. Perhaps its greatest hit was the widely believed claim that a secret U.S. government lab created AIDS. A Soviet telegram explaining the operation may sound familiar to those following COVID-19 news today:

The goal of these measures is to create a favorable opinion for us abroad that this disease is the result of secret experiments with a new type of biological weapon by the secret services of the USA and the Pentagon that spun out of control.

That narrative was initially placed in a pro-Soviet Indian newspaper by way of a whistleblower-style anonymous “letter to the editor” in 1983. It spread through newspapers in 80 countries over a period of four years; the Soviets occasionally revived it with relevant twists for whatever local media environment was of strategic interest. But in the era of Facebook and WeChat, these stories become a high-speed information virus themselves, and the murky source of the initial claim disappears as messages spread across chat groups.

State media outlets rarely transmit conspiracies in the form of bold, direct claims. They usually do it through a combination of insinuations: We’re just asking questions, really. This sometimes happens via interviews with conspiracy-theorist guests who claim they’ve been silenced by their own government, or publishing provocative headlines. Russia has elevated this to an art form, with the English-language RT and Sputnik networks regularly featuring those purportedly censored by the American media.

While easy to mock, tinfoil-hat diplomacy serves a purpose for China. Domestically, it’s allowed the Communist Party to distance itself from its own failings by reframing a poorly managed crisis as something that was inflicted on the Chinese people by outsiders. And Chinese state media are far from the only state source “just asking questions” during this pandemic. RT is hosting American kooks who allege on social media that the virus is part of a mass-vaccination campaign masterminded by Bill Gates, while Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is referencing claims that the virus was “specifically built for Iran using the genetic data of Iranians.” Americans aren’t above this kind of rumor mongering. Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas darkly noted the existence of a Wuhan “biosafety level-four super laboratory” in comments on Twitter and to the media, speculating that COVID-19 is a Chinese bioweapon. But neither mainstream American media nor U.S. government-sponsored entities such as Voice of America are pushing conspiracies as a public-diplomacy strategy. U.S. leaders are, however, demanding increased attention to the information war: Senators Mitt Romney, Marco Rubio, and Cory Gardner are calling for a task force to counter Chinese propaganda, and to provide U.S. embassies with guidance on how to counter false narratives locally.

The tension from the information war between the United States and China on the origin of COVID-19 has resulted in increased political brinkmanship; Trump’s administration has requested that the United Nations Security Council include a statement verifying that the virus originated in China in a COVID-19 resolution. Diplomats have been summoned. U.S. reporters have lost press credentials in China. This is not an ideal state of relations at any time, let alone during a pandemic that requires international cooperation.

But letting these narratives spread unchallenged is also not an option. Social-media companies should be paying far closer attention to the stories they’re allowing state-media propagandists to pay to boost. Allowing misleading narratives to take hold during a pandemic can cause immeasurable harm, and risks turning the major tech platforms into accomplices in the deliberate spread of lies. We must keep the focus on finding cures, not fighting over conspiracies.

No comments:

Post a Comment