- Fears were widespread in 1997 that handover would mean the end of Hong Kong’s freedoms but this didn’t happen because the capitalist city was valuable to China

- Given this is still the case today, Beijing must not ignore international alarm over the new law and apply it narrowly.

On the historic night of the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from British to Chinese sovereignty, a grave and breathless correspondent from a leading US television network stood with his back to a highway as armoured PLA trucks trundled past.

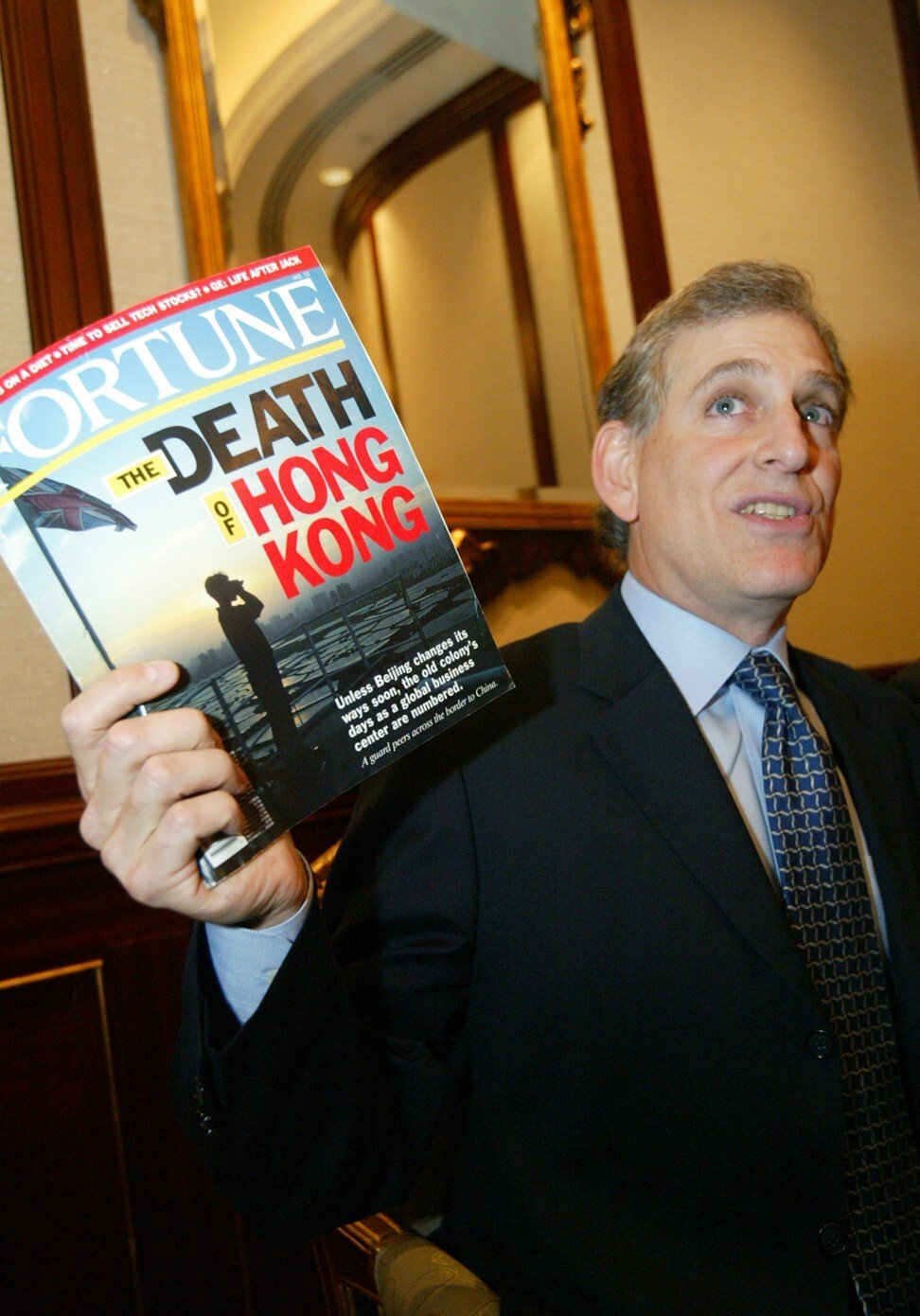

The gist of his commentary was clear: as thousands of troops from the People’s Liberation Army tonight pour across the border into Hong Kong, we mark the solemn end of freedom in this tiny territory. It was a narrative launched by Fortune’s “The Death of Hong Kong” cover story in July 1995, and it continues today.

What these reports did not record is that once the PLA troops had trundled nocturnally into their barracks, vacated just hours earlier by British troops, they were almost never seen again. That remains as true today as ever. The muscular exertion of national power predicted by so many commentators never happened.

Forecasts of extensive interference also failed to materialise. Hong Kong people were – as promised – left to rule Hong Kong.

Relentless encroachment on Hong Kong’s “high degree of autonomy” did not occur. Hong Kong’s internationally trusted common law legal system continued to operate, overseen by judges drawn from common law jurisdictions across the world. Freedom of speech expressed through Hong Kong’s infamously cantankerous media continued unabated.

Then American Chamber of Commerce chairman Steve Marcopoto holds up a copy of the July 1997 Fortune magazine edition with the cover “The Death of Hong Kong” during a lunch in Pacific Place on January 18, 2006. By then, many of the worst predictions for Hong Kong had failed to materialise. Photo: David Wong

Then American Chamber of Commerce chairman Steve Marcopoto holds up a copy of the July 1997 Fortune magazine edition with the cover “The Death of Hong Kong” during a lunch in Pacific Place on January 18, 2006. By then, many of the worst predictions for Hong Kong had failed to materialise. Photo: David WongWithout question, this all stuck in the craw of leaders in Beijing. But it was tolerated for a simple set of reasons: unlike the outgoing colonial administration which regarded Hong Kong as a distant and insignificant liability, Beijing really needed Hong Kong and the indispensable role it played linking the mainland economy with a large, complex global economy.

If a “high level of autonomy” was the price to be paid for access to global capital markets, and to a rich pool of legal, accounting and financial expertise that could familiarise China’s new generation of technocrats with the ways of the capitalist world and its institutions, then so be it.

- That Faustian compromise remains as pivotal today as it was in 1997, and calls into question the Armageddon alarms that this week greeted the release of a for Hong Kong.

For Beijing, “one country, two systems” sanctions radically different systems and behaviours within Hong Kong, giving the mainland economy access to and insights into the global economy it fervently wants to be a member of, but without forcing systemic changes within China itself that would be disruptive and divisive.

That is why, when mainland officials say today that they remain committed to the “one country, two systems” autonomies embedded in Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, they really mean it.

Not out of any sentimental sympathy for our freedoms, which for sure regularly test their patience, but because they really need Hong Kong to be different, and for sceptical outsiders to recognise that difference.

Put these factors together, and that is why Fortune and the innumerable other doomsayers about Hong Kong were wrong in 1997, and probably remain just as wrong today, about the death of Hong Kong and Beijing’s behaviour here.

In an angry editorial on Thursday, the Financial Times scoffed at Hong Kong’s business leaders who “are eager to believe that the [security] law will be narrowly applied” and said, “Sadly, however, there is little reason to believe that Beijing will apply it with restraint.”

European Council president Charles Michel speaks during a press conference in Brussels following a virtual summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang on June 22. The EU has repeatedly expressed its strong concerns about the national security law. Photo: European Council/DPA

European Council president Charles Michel speaks during a press conference in Brussels following a virtual summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang on June 22. The EU has repeatedly expressed its strong concerns about the national security law. Photo: European Council/DPAOn the contrary, Beijing has good reasons to apply the law narrowly, once you recognise its need for Hong Kong to perform well and efficiently in the process of serving the country’s economic interests at this extremely challenging time.

It is motivated to eliminate the chaos that the smooth running of the economy through half of 2019, and threatened to infect the in Guangdong.- It is motivated by the manifest incapacity of the local Hong Kong administration to tackle the community’s challenges. It is motivated by signs that protesters were no longer simply calling for democratic freedoms, but for – a red line for Beijing.While so many overseas have shown profound prejudice in leaping Beijing’s introduction of the security law, and while I believe their judgments are wrong about Beijing’s incentives to apply the new law with restraint, there should be no doubt that international alarm is legitimate. Beijing would be foolish to disregard the many detailed concern.Hong Kong finds itself today in a more precarious place than at any point since the 1984 signing of the . As at every stage of the four-decade transition back to Chinese sovereignty, Hong Kong’s community has remained deeply divided over the contract agreed by London and Beijing over their heads.

All efforts by Beijing over the past 23 years to win hearts and minds have done little to reduce these divides. And, of course, the decision to impose a security law – no matter how reasonable from the point of view of any sovereign government – can only aggravate them.

If they are ever going to be resolved – and it is likely to take years – there needs to be respect for the legitimate divisions within Hong Kong and for the deep-seated differences between Hong Kong and the mainland.

If President Xi Jinping’s team want to prevent this initiative from becoming a global diplomatic disaster, then sensitivity is going to be needed by the bucketload.

The creation on Hong Kong soil of an , which answers directly to Beijing, is going to require acutely sensitive management. A right to decide that certain cases should be heard by mainland courts creates highly flammable possibilities. Anti-government protesters halt on Hennessy Road in Causeway Bay on July 1, the 23rd anniversary of the handover, during a march against the national security law that went ahead despite a police ban. Photo: Sam Tsang

Anti-government protesters halt on Hennessy Road in Causeway Bay on July 1, the 23rd anniversary of the handover, during a march against the national security law that went ahead despite a police ban. Photo: Sam TsangAbove all else, the law must be used sparsely, and with extreme justification. If it in any way threatens the freedoms enshrined in the Basic Law, then the fate of Hong Kong is truly in jeopardy.

As the Post said in on June 3: “The law is meant to plug loopholes rather than end our freedoms and civil liberties. The world needs to be shown that the ‘two systems’ has not been undermined.”Only time will tell. The Legislative Council election in September may be a litmus test. In the meantime, wariness is in order.

No comments:

Post a Comment