Things unraveled the usual way.

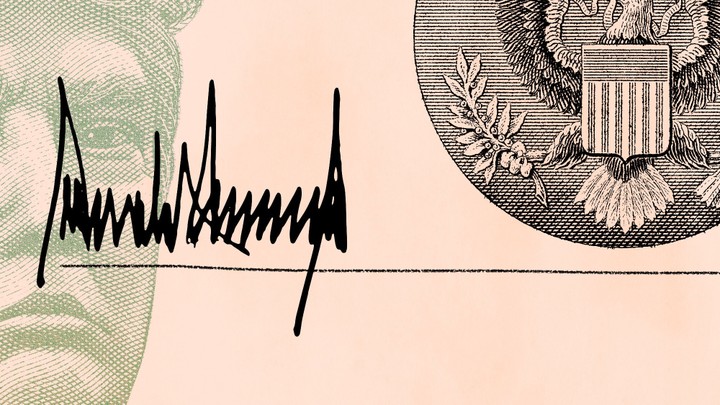

Earlier this week, President Donald Trump tweeted that whether to “open up the states” and restart the economy “is the decision of the President,” not state governors. He doubled down on his position at an afternoon White House news conference, where he added that, as president, he has “total” authority on the subject. Fact-checkers and legal experts rushed to repudiate the claim, citing, as usual, both the Constitution and Trump’s own prior statements. Trump lacks the legal authority to override the safety measures put in place by the states, they pointed out, and his tweets are inconsistent with his own insistence earlier this month that it’s up to state governors whether to impose the lockdowns in the first place.

The commentators aren’t wrong. But the interesting question is not really whether Trump has constitutional footing to forcibly compel states and municipalities to rescind the lockdown orders, but why he is inclined to assert that the decision to do so lies with him. And the even more interesting question is what powers Trump could, within his constitutional bounds, invoke to get businesses back open and Americans back on the streets.

Trump’s claim that he can unilaterally restart the economy is legally hard to square with his decision not to issue national lockdown guidance and to place the onus for such decisions on state governors. But politically, the two positions can be reconciled. An administration attuned to the latest public-health data on the coronavirus threat might be expected to move decisively toward a lockdown and to exhibit caution and incrementalism in advising rollbacks. Call it the London Breed model, for the San Francisco mayor now being lauded for declaring a citywide emergency and banning large gatherings back in February, in the face of intense political flak and well before most of the rest of the country’s leaders took action. An administration that views the risks and rewards of its response primarily through unemployment figures, however, might be expected to take the opposite tack—that is, hesitate to recommend widespread lockdown measures for fear of being blamed for the financial fallout and then seek a conspicuous role in easing those measures in the hopes of reaping the political upside that comes with an economic rebound. This is the Trump model.

Whatever Trump’s political calculus in claiming authority over the decision to reopen the country, his ability to follow up with substantive action is significant, though bounded. Trump cannot force governors and mayors nationwide to rescind their shelter-in-place orders, but he has other options for shaping the public’s perception of and ability to seek reprieve from the coronavirus threat, as well as the states’ capacity to manage the threat.

He could appeal directly to the public and convince Americans that it’s time to get back to work, thereby creating pressure for states and cities to loosen existing restrictions and surely affecting policy on the ground in Republican-led states such as Florida, whose governor resisted action for weeks and explicitly looked to the White House for instruction before finally issuing his stay-at-home order. Trump could mandate a shift in the federal government’s messaging—that includes not only the president’s own coronavirus guidelines but also Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance relied on by states, the general public, schools, businesses, health-care providers, and first responders. His agencies could continue to calibrate the many rules and interpretations they are charged with issuing to implement the programs and initiatives laid out in Congress’s stimulus bill, affecting matters as fundamental as which employees can take sick leave and for how long, and businesses’ incentive to retain rather than lay off workers. And Trump has great discretion in the ongoing disbursement of relief funds and allocation of national resources to the states.

For two very different camps, those anxious about what Trump might do and those eager to defend him for not doing enough, the temptation is to fixate on the outer limits of the president’s powers—such as Trump’s inability to forcibly impose or lift lockdown measures—while giving short shrift to the many courses of action well within the executive branch’s purview. This kind of lopsided thinking is evident even among proponents of expansive executive power. For instance, the legal scholar John Yoo recently argued that the states bear the brunt of the responsibility for responding to the pandemic, because only they have the authority, and manpower, to forcibly restrict the physical movements of the citizenry, and that the federal government’s authority is confined to “truly national problems.” That position extrapolates too much from the bare fact that quarantine powers lie with the states, and overlooks all the ways and all the stages at which the federal government has been uniquely positioned to effectuate—or stymie—a coordinated response to an unfolding international health crisis.

The bottom line is that the president’s powers are immense, and particularly so in the midst of an emergency whose outcome so clearly hinges on the country’s ability to get on the same page about which sacrifices are necessary and for how long. Trump has indicated his intention to reopen the economy, and soon. There is plenty he could do to make good on that intention, including over the recommendations of his own medical experts, and not much comfort to be derived from what he can’t.

No comments:

Post a Comment