The first person diagnosed with COVID-19 in Italy was a healthy 38-year-old who arrived at his local emergency room in Codogno, south of Milan, with flu-like symptoms. His condition quickly worsened, and doctors had the foresight to test him for the coronavirus. On February 20, his results came back positive. Within days, Codogno and other nearby towns in the region of Lombardy were on lockdown, and within weeks so was the entire country.

Patient One—for privacy reasons, we know just his first name, Mattia—spent weeks on a ventilator before he could breathe on his own again, and was released from the hospital only on March 22. In Italy, Mattia is most often portrayed as a success story, a story of resilience, in a country where more than 21,000 people have died from the coronavirus and some good news is needed. “Mattia teaches us that you can also recover from serious illness,” Raffaele Bruno, the head of infectious diseases at the San Matteo Hospital in Pavia, where Mattia was treated, told me.

But his story is also in some ways unsettling. While Mattia was still in the hospital, his father died of COVID-19, and his wife, nearly eight months pregnant, tested positive as well, though she eventually recovered. Mattia turned out to be a “super-spreader” who infected scores of others, including in his amateur soccer league, and at the hospital where he was diagnosed. His is a cautionary tale of asymptomatic contagion and the unpreparedness of hospitals. In an audio message after his release, Mattia urged his fellow Italians to stay inside, and said he was lucky to have been treated in the early days of the outbreak, before Lombardy started running low on ventilators. (Officials believe Italy’s Patient Zero, the first person to have brought COVID-19 to the country, is likely a German who traveled to northern Italy around January 25. I use the terms Patient One and Patient Zero cautiously: They’re important concepts in epidemiology, but morally complex—outbreaks have multiple causes, and we don’t want to stigmatize the infected.)

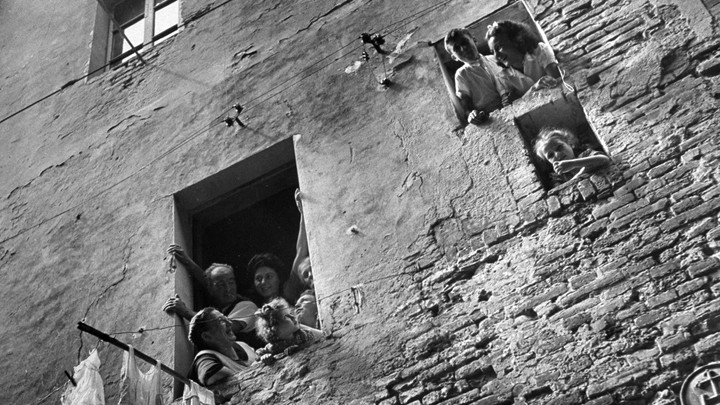

I see something else in Mattia’s experience—a story of pathos, in which life and death, pain and resilience are intertwined. Italy is a place of intricate family and community ties. Two and three generations often live in the same city, the same neighborhood, or even the same apartment building. People commute by train to other cities for work, while keeping their residence, and their family, in their hometowns, where a network of relatives can help raise their children. Without the extensive state-supported childcare of France and other European countries, many Italian grandparents are the primary babysitters, allowing parents to work and keep the gears of the economy turning. These ties are strong in Italy, where reliance on the family is typically greater than on the state.

They are also part of what put the country, with the second-oldest population in the world, after Japan, at such mortal risk, as contagion spread among relatives. It’s a pattern that is now being repeated around the world—especially in countries and cultures where large extended families are the rule, not the exception, and in lower-income communities in which people live in close quarters, where social distancing is fine in theory but nearly impossible in practice. All this bears a strange irony—in the recognition that for those of us able to look after ourselves, being alone, away from other humans, from our kin, is probably safer than being together. Controlling the pandemic will reshape family life for a long time to come.

Bruno told me that knowing whether Mattia infected his own father, or any of his other relatives, is “impossible.” Still, the sense of guilt that particular possibility might involve—or the generalized survivor guilt of weathering the pandemic when other family members or friends don’t—is something that will likely grow. “There’s a strong sense of shame and guilt that’s been underestimated,” David Lazzari, the president of Italy’s National Council of Psychologists, told me. “It often compels people to hide their symptoms, because maybe they’re afraid of identifying themselves as a carrier of the virus and then as someone who infects others.” Imagine, he continued, how people will live in the aftermath “with the idea that they infected half the town.” A lot of post-traumatic stress will ensue, he said. Now the pain is more immediate: a sense of powerlessness. Mourning without funerals. And being separated from the people we love. “We need to show our closeness, but from a distance,” Lazzari said.

For weeks now, I’ve been thinking about Patient One, from my apartment in Paris, where I live alone. All of us living far away from loved ones, especially older and more vulnerable relatives, have had to think long and hard about how best to offer support. Our immediate instinct is to want to gather together, to show closeness. Yet that is now the worst thing we could possibly do. Governments in France and Israel, where generations of families also tend to live in close proximity, have ordered older people to stay home, and told grandchildren to steer clear. In Germany, some health experts have suggested that children not see their grandparents until well into the fall, or even after Christmas. In Britain, where the government has told citizens to save lives by staying home, a cabinet minister was criticized for visiting his own parents.

Showing closeness from a distance requires overturning our most basic understanding of human contact and connection. But we have to stay distant, no matter how anathema that is to our world view. At least that’s what I like to tell myself, half a world away from my family in the United States. Weeks ago, the State Department raised its global travel advisory to its highest level—“Do Not Travel,” the ranking typically assigned to war zones—and began issuing warnings for American citizens to “arrange for immediate return to the United States unless they are prepared to remain abroad for an indefinite period.” But where was home? And how long was an indefinite period?

One of my closest friends in Paris, who is also American, gamed it out: If you went back to the U.S., he reasoned, you’d have to self-quarantine for two weeks when you got there. And if someone you loved were dying, you couldn’t actually be with them anyway. I had been reading L’Eco di Bergamo, the paper of a province north of Milan, with its 10 daily pages of square-inch-size obituaries, in which many of the dead were remembered as loving grandparents. I already understood, well before the reality set in in the United States, that when you die of COVID-19, you die alone. This truth was nearly impossible to bear.

I stayed in Paris—my life is here, my work is here, and I’m grateful my apartment has an unobstructed view of the sky. I called my parents and told them not to leave the house, not even to go to the grocery store. At the time, there were three presumptive COVID-19 cases in the state where they live. Doesn’t matter, I told them. The day before Mattia was diagnosed, Italy had no known cases. I called other relatives in the U.S., who were already hunkering down in their respective cities.

My solitude is not unendurable. I may be on my own here, but I’m in daily contact with friends and family around the world. We compare notes on lockdown measures. Some confide that they’re struggling—depressed, anxious, sometimes furious with their partners and children, worried about their unstable finances, angry at the world. I wish I could do something, at least babysit; instead, I listen. Everyone is scared. Has there ever been another moment when so many of us shared the same forebodings at the same time? I’m familiar with grief and existential powerlessness. I’ve wrestled, and tried to make peace, with loss. I’ve also worked from home, remotely, for years, and know how misunderstandings can be amplified with distance, and how hard reading the room is when there is no room.

We need to show our closeness, but from a distance. On a new weekly Zoom call with my entire extended family, a cousin recalled that my adored Great Aunt Natalie once shared with him her childhood memories of people walking around in masks during the 1918 flu pandemic. Aunt Nat had wanted to be a newspaper reporter but after high school, she wound up working as a stenographer and selling classified ads for the Cleveland Press to support her widowed mother and her two sisters during the Great Depression. How strange that the youngest generation in my family will also have childhood memories of adults wearing masks.

I think again of Mattia, the infector who survived. So much pathos and trauma, but also joy. Last week his wife gave birth to their daughter, Giulia. What kind of world will she inherit? I see my niece and nephew on screens. Sometimes I cannot even bear to call, because afterward, I miss their fierce faces and remember the feeling of their little warm bodies when we’d curl up together on the sofa to read books. This is now the price we pay for maintaining a safe distance, never knowing whether a physical visit might be a comfort or a threat. Everyone is so close but so impossibly far.

No comments:

Post a Comment